Epigraph: “And as for the man who steals and the woman who steals, cut off their hands in retribution of their offence as an exemplary punishment from Allah. And Allah is Mighty, Wise.” (Al Quran 5:39)

What is the significance of these large pillars? Read in the Epilogue

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD

It is amazing that Europeans over the last few centuries have been vehemently critical of the punishment of cutting of a hand for theft, which could be reduced to cutting of a finger or interpreted in a metaphorical sense and have conveniently forgotten their trials by ordeal. Let me quote from an article, Justice, medieval style:

For the better part of a millennium, Europe’s legal systems decided difficult criminal cases in a most peculiar way. When judges were uncertain about an accused criminal’s guilt, they ordered a cauldron of water to be boiled, a ring to be thrown in, and the defendant to plunge in his naked hand and pluck the object out. The defendant’s hand was wrapped in bandages and revisited three days later. If it survived the bubbling cauldron unharmed, the defendant was declared innocent. If it didn’t, he was convicted.

These trials were called “ordeals.” They reached their height between the 9th and 13th centuries, and the methods varied. In one variant, a piece of iron was heated until it was red hot. The defendant picked it up and carried it with her bare hand. In another, the defendant was stripped naked, his hands and feet bound, and he was pushed into a pool of holy water. If the defendant sank, he was acquitted. If he floated, he was condemned.[1]

The Encyclopedia Britannica has the following to say about Trial by ordeal:

The ordeal by physical test, particularly by fire or water, is the most common. In Hindu codes a wife may be required to pass through fire to prove her fidelity to a jealous husband; traces of burning would be regarded as proof of guilt. The practice of dunking suspected witches was based on the notion that water, as the medium of baptism, would “accept,” or receive, the innocent and “reject,” or buoy, the guilty.[2]

Since Constantine I (272 CE – 337 CE) converted to Christianity in the early 4th century, Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire, so, whatever was common practice during the Dark Ages in Europe, was with explicit or implicit consent of the bureaucracy of the Catholic Church until the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century.

It was not until the 12th and early 13th century that Pope Innocent III (1161 – 1216), after the first three Crusades and constant interaction with Islam for decades, woke up to the horrors of these practices of trial by ordeal.

Here is a short clip from a documentary, by the History Channel, the Dark Ages, which talks about trial by ordeal towards the end of the clip in reference to the time frame of Clovis I (466 CE – 511 CE):

First a few words about Clovis I (466 CE – 511 CE):

Shortly before his death, Clovis called a synod of Gallic bishops to meet in Orléans to reform the Church and create a strong link between the Crown and the Catholic episcopate. This was the First Council of Orléans. Thirty-three bishops assisted and passed 31 decrees on the duties and obligations of individuals, the right of sanctuary and ecclesiastical discipline. These decrees, show that the politics of Clovis were always married to the Catholic Church.

Clovis I is traditionally said to have died on 27 November 511; however, the Liber Pontificalis suggests that he was still alive in 513. After his death, Clovis was laid to rest in the Abbey of St Genevieve in Paris. His remains were relocated to Saint Denis Basilica in the mid- to late-18th century. In other words he has always been celebrated by the Catholic Church.

Upon his death his realm was divided among his four sons: Theuderic, Chlodomer, Childebert, and Clotaire.

Epilogue

In this historic context, if we begin to look at the teaching of cutting of a hand of a thief, with its varied interpretations, rather than finding it barbaric, we find it, to be the one that created law and order in human societies, over the centuries. Especially, when we take into consideration the fact that most medieval societies did not have resources to provide humane conditions in prison systems.

Many of us in the West have seen the deterrent effect of financial penalties and high interest rates, for failing to pay federal taxes in time. On several occasions, I have paid, almost 10% of the money due, as fines, to the Government, for delay of as little as a day, in paying withheld taxes of my employees. It has certainly created respect and awe of Law in my mind and has shaped my practice of making it a priority to pay in time.

In a broad context, these penalties can be considered to be part of the metaphorical domain of, ‘cut off their hands,’ to deter late or missing payments.

Cutting hands of thieves, even if taken literally, in the present day circumstances, can certainly be interpreted in milder tones and mean cutting of a little finger in a modern operating room or a short jail term, as is mentioned in the Holy Quran that Allah is the Gracious and the Merciful and He is the Most Forgiving, scores if not hundreds of times. There is a Hadith in the Book of Bukhari, “Allah’s mercy surpasses or far outweighs His anger.”

In a recent informal discussion at a dinner table, with my friends, I asked half jokingly, God forbid, if one of them was convicted of theft and given a choice of a finger cut off or ten years in a federal prison in USA, which one would they prefer. To my surprise I did not find any takers for 10 years of prison, which they would otherwise tout as very civilized, modern and humane punishment!

Why are the government buildings built in majestic architecture, rather than with an intent of saving the tax payers’ money? The construction of most supreme courts around the world, with large pillars and other giant structures, is meant to create awe in the hearts and minds of common man, to create a deterrent effect against crime or disorder. So deterrence is no stranger to our modern minds.

Once we look at any Islamic teaching, without hype and prejudice and compare apples with apples, we find Islamic teachings, if interpreted properly, to be very profound and find in them great utilitarian value.

To read about the Utilitarian purpose of the Islamic teachings.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia about Trial by ordeal:

Trial by ordeal is a judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused is determined by subjecting him to an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience. Classically, the test is one of life or death and the proof of innocence is survival. In some cases, the accused is considered innocent if he escapes injury or if his injuries heal.

In medieval Europe, like trial by combat, trial by ordeal was considered a judicium Dei: a procedure based on the premise that God would help the innocent by performing a miracle on his behalf. The practice has much earlier roots, however, being attested as far back as the Code of Hammurabi and the Code of Ur-Nammu, and also in animist tribal societies, such as the trial by ingestion of “red water” (calabar bean) in Sierra Leone, where the intended effect is magical rather than invocation of a deity’s justice.

In pre-modern society, the ordeal typically ranked along with the oath and witness accounts as the central means by which to reach a judicial verdict. Indeed, the term ordeal, Old English ordǣl, has the meaning of “judgment, verdict” (German Urteil, Dutch oordeel), from Proto-Germanic *uzdailjam “that which is dealt out”.

According to a theory put forward by Peter Leeson, trial by ordeal was surprisingly effective at sorting the guilty from the innocent.[1] Because defendants were believers, only the truly innocent would choose to endure a trial; guilty defendants would confess or settle cases instead. Therefore, the theory goes, church and judicial authorities would routinely rig ordeals so that the participants—presumably innocent—could pass them. If this theory is correct, medieval superstition was actually a useful motivating force for justice.[2]

Priestly cooperation in trials by fire and water was forbidden by Pope Innocent III at the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 and replaced by compurgation, later by inquisition.[3] Trials by ordeal became rarer over the Late Middle Ages, often replaced by confessions extracted under torture, but the practice was discontinued only in the 16th century.

Contents |

Ordeal of fire

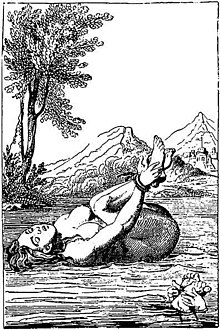

After being accused of adultery Cunigunde of Luxembourg proved her innocence by walking over red-hot ploughshares.

Ordeal of fire typically required that the accused walk a certain distance, usually nine feet, over red-hot ploughshares or holding a red-hot iron. Innocence was sometimes established by a complete lack of injury, but it was more common for the wound to be bandaged and re-examined three days later by a priest, who would pronounce that God had intervened to heal it, or that it was merely festering—in which case the suspect would be exiled or executed. One famous story about the ordeal of ploughshares concerned Edward the Confessor‘s mother, Emma of Normandy. According to legend, she was accused of adultery with Bishop Ælfwine of Winchester, but proved her innocence by walking barefoot unharmed over burning ploughshares.

Another form of the ordeal required that an accused remove a stone from a pot of boiling water, oil, or lead. The assessment of the injury and the consequences of a miracle or lack of one, followed a similar procedure to that described above. An early (non-judicial) example of the test was described by Gregory of Tours in the 7th century. He describes how a Catholic saint, Hyacinth, bested an Arian rival by plucking a stone from a boiling cauldron. Gregory accepted that it took Hyacinth about an hour to complete the task (because the waters were bubbling so ferociously), but he was pleased to record that when the heretic tried, he had the skin boiled off up to his elbow.

During the First Crusade, the mystic Peter Bartholomew went through the ordeal by fire in 1099 by his own choice to disprove a charge that his claimed discovery of the Holy Lance was fraudulent. He died as a result of his injuries.

Ordeal of water

English common law

In the Assize of Clarendon, enacted in 1166 and the first II of England|Henry II]], the law of the land required that: “anyone, who shall be found, on the oath of the aforesaid [a jury], to be accused or notoriously suspect of having been a robber or murderer or thief, or a receiver of them … be taken and put to the ordeal of water.”[4]

Ordeal of boiling water

First mentioned in the 6th century Lex Salica, the ordeal of hot water requires the accused to dip his hand in a kettle of boiling water and retrieve a stone.

King Athelstan made a law concerning the ordeal. The water had to be about boiling, and the depth from which the stone had to be retrieved was up to the wrist for one accusation and up to the elbow for three. The ordeal would take place in the church, with several in attendance, purified and praying God to reveal the truth. Afterwards, the hand was bound and examined after three days to see whether it was healing or festering.[5]

This was still a practice of 12th century Catholic churches: the priest would demand a suspect to place his hand in the boiling water. If after three days, God had not healed his wounds, the suspect was guilty of the crime.[6]

Ordeal of cold water

The ordeal of cold water has a precedent in the Code of Ur-Nammu and the Code of Hammurabi, under which a man accused of sorcery was to be submerged in a stream and acquitted if he survived. The practice was also set out in Frankish law but was abolished by Louis the Pious in 829. The practice reappeared in the Late Middle Ages: in the Dreieicher Wildbann of 1338, a man accused of poaching was to be submerged in a barrel three times and to be considered guilty if he sank to the bottom.

Gregory of Tours recorded in the 6th century the common expectation that with a millstone round the neck, the guilty would sink: “The cruel pagans cast him [Quirinus, bishop of the church of Sissek] into a river with a millstone tied to his neck, and when he had fallen into the waters he was long supported on the surface by a divine miracle, and the waters did not suck him down since the weight of crime did not press upon him.”[7]

Witch-hunts

Ordeal by water was later associated with the witch-hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries, although in this scenario the outcome was reversed from the examples above: an accused who sank was considered innocent, while floating indicated witchcraft. Demonologists developed inventive new theories about how it worked. The ordeal would normally be conducted with a rope holding the subject connected to assistants sitting in a boat or the like, so that the person being tested could be pulled in if he/she did not float; the notion that the ordeal was flatly devised as a situation without any possibility of live acquittal, even if the outcome was ‘innocent’, is a modern elaboration. Some argued that witches floated because they had renounced baptism when entering the Devil‘s service. Jacob Rickius claimed that they were supernaturally light and recommended weighing them as an alternative to dunking them.[8] King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England) claimed in his Daemonologie that water was so pure an element that it repelled the guilty. A witch trial including this ordeal took place in Szeged, Hungary as late as 1728.[9]

The ordeal of water is also contemplated by the Vishnu Smrti,[10] which is one of the texts of the Dharmaśāstra.[11]

Ordeal of the cross

The ordeal of the cross was apparently introduced in the Early Middle Ages by the church in an attempt to discourage judicial duels among the Germanic peoples. As with judicial duels, and unlike most other ordeals, the accuser had to undergo the ordeal together with the accused. They stood on either side of a cross and stretched out their hands horizontally. The one to first lower his arms lost. This ordeal was prescribed by Charlemagne in 779 and again in 806. A capitulary of Louis the Pious in 819[12] and a decree of Lothar I, recorded in 876, abolished the ordeal so as to avoid the mockery of Christ.

Ordeal of ingestion

Franconian law prescribed that an accused was to be given dry bread and cheese blessed by a priest. If he choked on the food, he was considered guilty. This was transformed into the ordeal of the Eucharist (trial by sacrament) mentioned by Regino of Prüm ca. 900: the accused was to take the Eucharist after a solemn oath professing his innocence. It was believed that if the oath had been false, the criminal would die within the same year.

Another version states: “The priest wrote the Lord’s Prayer on a piece of bread, of which he then weighed out ten pennyweights, and so likewise with the cheese. Under the right foot of the accused, he set a cross of poplar wood, and holding another cross of the same material over the man’s head, threw over his head the theft written on a tablet. He placed the bread and cheese at the same moment in the mouth of the accused, and, on doing so, recited the conjuration: ‘I exorcize thee, most unclean dragon, ancient serpent, dark night, by the word of truth, and the sign of light, by our Lord Jesus Christ, the immaculate Lamb generated by the Most High, that bread and cheese may not pass thy gullet and throat, but that thou mayest tremble like and thou mayest tremble like an aspen-leaf, Amen; and not have rest, O man, until thou dost vomit it forth with blood, if thou hast committed aught in the matter of the aforesaid theft.'”

Numbers 5:12–27 prescribes that a woman suspected of adultery should be made to swallow “the bitter water that causeth the curse” by the priest in order to determine her guilt. The accused would be condemned only if ‘her belly shall swell and her thigh shall rot’. It is known as the Sotah. One writer has recently argued that the procedure has a rational basis, envisioning punishment only upon clear proof of pregnancy (a swelling belly) or venereal disease (a rotting thigh).[13]

Ordeal of poison

Some cultures, such as the Efik Uburutu people of present-day Nigeria, would administer the poisonous calabar bean (known as “esere” in Efik) in an attempt to detect guilt. A defendant who vomits up the bean is innocent. A defendant who becomes ill or dies is considered guilty.[14]

Residents of Madagascar could accuse one another of various crimes, including theft, Christianity and especially witchcraft, for which the ordeal of tangena was routinely obligatory. In the 1820s, ingestion of the poisonous nut caused about 1,000 deaths annually. This average rose to around 3,000 annual deaths between 1828 and 1861.[15]

Ordeal of boiling oil

Trial by boiling oil has been practiced in villages in India[16] and in certain parts of West Africa, such as Togo.[17] There are two main alternatives of this trial. In one version, the accused parties are ordered to retrieve an item from a container of boiling oil, with those who refuse the task being found guilty.[16] In the other version of the trial, both the accused and the accuser have to retrieve an item from boiling oil, with the person or persons whose hand remains unscathed being declared innocent.[17]

Other ordeal methods

An Icelandic ordeal tradition involves the accused walking under a piece of turf. If the turf falls on the accused’s head, the accused person is pronounced guilty.[18]

See also

- Bisha’a – trial by ordeal among the Bedouin

- Running the gauntlet

- subpoena ad testificandum

- subpoena duces tecum

Notes

- ^ Peter Leeson, “Ordeals.”

- ^ Peter Leeson, “Justice, Medieval Style,” Boston Sunday Globe, January 31, 2010.

- ^ Vold, George B., Thomas J. Bernard, Jeffrey B. Snipes (2001). Theoretical Criminology. Oxford University Press.

- ^ The Assize of Clarendon, as published in English Historical Documents v ii 1042—1189, D C Douglas editor, Oxford University Press, London 1981, p 441.

- ^ Medieval Sourcebook: The Laws of King Athelstan AD 924-939

- ^ Medieval Sourcebook: Ordeal of Boiling Water, 12th or 13th Century

- ^ Historia Francorum i.35

- ^ Superstition and Force, Henry C. Lea, 1866

- ^ Böhmer, ius eccles. 5.608

- ^ Sacred Books of the East, vol. 7, tr. Julius Jolly, chapter 12

- ^ XII.

- ^ MGH, Capitularia regum Francorum, c. 138, 27.

- ^ Sadakat Kadri, The Trial: Four Thousand Years of Courtroom Drama (Random House, 2006), p.25.

- ^ “Calabar Bean”. Flora Delaterre.

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (October 1991). “The state and pre-colonial demographic history: the case of nineteenth century Madagascar”. Journal of African History 23 (3): 415–445.

- ^ a b “Men undergo trial by boiling water over stolen food”. The Irish Independent. 19 September 2006.

- ^ a b “Justice”. Taboo. episode 1. season 2. 6 October 2003.

- ^ Miller, William Ian. “Ordeal in Iceland,” Scandinavian Studies Issue 60, 1988. pp. 189-218

References

- H. Glitsch, Mittelalterliche Gottesurteile, Leipzig (1913).

- Kaegi, Alter und Herkunft des germanischen Gottesurteils (1887).

- Henry C. Lea Superstition and Force (Greenwood, 1968; reprint of 1870 edition.)

- Sadakat Kadri The Trial: A History from Socrates to O.J. Simpson (Random House, 2006).

- Ian C. Pilarczyk, “Between a Rock and a Hot Place: Issues of Subjectivity and Rationality in the Medieval Ordeal by Hot Iron”, 25 Anglo-American Law Rev. 87-112 (1996). http://iancpilarczyk.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/BetweenARock.pdf

- Robert Bartlett, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal, New York: Clarendon Press, 1986.

- William Ian Miller, “Ordeal in Iceland,” Scandinavian Studies 60 (1988): 189-218.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ordeal |

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online “Ordeal”

- http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/ordeals1.html

- http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/water-ordeal.html

“Ordeals“. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

“Ordeals“. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

My References

1. http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2010/01/31/justice_medieval_style/?page=1

2. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/431352/ordeal

Categories: Europe, Highlight, Law and Religion, Law Enforcement

Very informative, logical article and well explained. This subject of cutting of hands comes up many times in conversation with some people. Thank you for providing this information.