Epigraph: “When seen in the historical context, Muhammad can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women’s rights.” William Montgomery Watt

| Rights |

|---|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by claimant |

| Other groups of rights |

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Women in Society |

|---|

|

Women’s rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls of many societies worldwide.

In some places these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behaviour, whereas in others they may be ignored or suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls in favour of men and boys.[1]

Issues commonly associated with notions of women’s rights include, though are not limited to, the right: to bodily integrity and autonomy; tovote (suffrage); to hold public office; to work; to fair wages or equal pay; to own property; to education; to serve in the military or be conscripted; to enter into legal contracts; and to have marital or parental rights.[2]

Contents

[hide]

- 1 History of women’s rights

- 2 Equal employment rights for women and men

- 3 Suffrage, the right to vote

- 4 Property rights

- 5 Modern movements

- 6 Natural law and women’s rights

- 7 Human rights and women’s rights

- 8 Rape and sexual violence

- 9 2011 study of status by country

- 10 See also

- 11 References

- 12 Sources

- 13 External links

History of women’s rights

Ancient cultures

While in many ancient cultures males seem to have dominated, there are some exceptions. For instance in the Nigerian Aka culture women may hunt, even on their own, and often control distribution of resources.[3] Ancient Egypt had female rulers, such as Cleopatra.

China

The status of women in China was low, largely due to the custom of foot binding. About 45% of Chinese women had bound feet in the 19th century. For the upper classes, it was almost 100%. In 1912, the Chinese government ordered the cessation of foot-binding. Foot-binding involved alteration of the bone structure so that the feet were only about 4 inches long. The bound feet caused difficulty of movement, thus greatly limiting the activities of women.

Due to the social custom that men and women should not be near to one another, the women of China were reluctant to be treated by male doctors of Western Medicine. This resulted in a tremendous need for female doctors of Western Medicine in China. Thus, female medical missionary Dr. Mary H. Fulton (1854–1927)[4] was sent by the Foreign Missions Board of the Presbyterian Church (USA) to found the first medical college for women in China. Known as the Hackett Medical College for Women (夏葛女子醫學院),[5][6] this College was located in Guangzhou, China, and was enabled by a large donation from Mr. Edward A.K. Hackett (1851–1916) of Indiana, USA. The College was aimed at the spreading of Christianity and modern medicine and the elevation of Chinese women’s social status.[7][8]

Greece

The status of women in ancient Greece varied form city state to city state. Records exist of women in ancient Delphi, Gortyn, Thessaly, Megara and Sparta owning land, the most prestigious form of private property at the time.[9]

In ancient Athens, women had no legal personhood and were assumed to be part of the oikos headed by the male kyrios. Until marriage, women were under the guardianship of their father or other male relative, once married the husband became a woman’s kyrios. As women were barred from conducting legal proceedings, the kyrios would do so on their behalf.[10] Athenian women had limited right to property and therefore were not considered full citizens, as citizenship and the entitlement to civil and political rights was defined in relation to property and the means to life.[11] However, women could acquire rights over property through gifts, dowry and inheritance, though her kyrios had the right to dispose of a woman’s property.[12] Athenian women could enter into a contract worth less than the value of a “medimnos of barley” (a measure of grain), allowing women to engage in petty trading.[10] Slaves, like women, were not eligible for full citizenship in ancient Athens, though in rare circumstances they could become citizens if freed. The only permanent barrier to citizenship, and hence full political and civil rights, in ancient Athens was gender. No women ever acquired citizenship in ancient Athens, and therefore women were excluded in principle and practice from ancient Athenian democracy.[13]

By contrast, Spartan women enjoyed a status, power, and respect that was unknown in the rest of the classical world. Although Spartan women were formally excluded from military and political life they enjoyed considerable status as mothers of Spartan warriors. As men engaged in military activity, women took responsibility for running estates. Following protracted warfare in the 4th century BC Spartan women owned approximately between 35% and 40% of all Spartan land and property.[14][15] By the Hellenistic Period, some of the wealthiest Spartans were women.[16] They controlled their own properties, as well as the properties of male relatives who were away with the army.[14] Spartan women rarely married before the age of 20, and unlike Athenian women who wore heavy, concealing clothes and were rarely seen outside the house, Spartan women wore short dresses and went where they pleased.[17] Girls as well as boys received an education, and young women as well as young men may have participated in the Gymnopaedia (“Festival of Nude Youths”).[14][18]

Plato acknowledged that extending civil and political rights to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state.[19] Aristotle, who had been taught by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that “nature has distinguished between the female and the slave”, but he considered wives to be “bought”. He argued that women’s main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle the labour of women added no value because “the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides”.[20]

Contrary to these views, the Stoic philosophers argued for equality of the sexes, sexual inequality being in their view contrary to the laws of nature.[21] In doing so, they followed the Cynics, who argued that men and women should wear the same clothing and receive the same kind of education.[21] They also saw marriage as a moral companionship between equals rather than a biological or social necessity, and practiced these views in their lives as well as their teachings.[21] The Stoics adopted the views of the Cynics and added them to their own theories of human nature, thus putting their sexual egalitarianism on a strong philosophical basis.[21]

Ancient Rome

Fulvia, the wife of Mark Antony, commanded troops during the Roman civil wars and was the first woman whose likeness appeared on Roman coins.[22]

Freeborn women of ancient Rome were citizens who enjoyed legal privileges and protections that did not extend to non-citizens or slaves.Roman society, however, was patriarchal, and women could not vote, hold public office, or serve in the military.[23] Women of the upper classes exercised political influence through marriage and motherhood. During the Roman Republic, the mother of the Gracchus brothers andof Julius Caesar were noted as exemplary women who advanced the career of their sons. During the Imperial period, women of the emperor’s family could acquire considerable political power, and were regularly depicted in official art and on coinage. Plotina exercised influence on both her husband, the emperor Trajan, and his successor Hadrian. Her letters and petitions on official matters were made available to the public —an indication that her views were considered important to popular opinion.[24]

A child’s citizen status was determined by that of its mother. Both daughters and sons were subject to patria potestas, the power wielded by their father as head of household (paterfamilias). At the height of the Empire (1st–2nd centuries), the legal standing of daughters differs little if at all from that of sons.[25] Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.[26]

Couple clasping hands in marriage, idealized by Romans as the building block of society and as a partnership of companions who work together to produce and rear children, manage everyday affairs, lead exemplary lives, and enjoy affection[27]

In the earliest period of the Roman Republic, a bride passed from her father’s control into the “hand” (manus) of her husband. She then became subject to her husband’s potestas, though to a lesser degree than their children.[28] This archaic form of manus marriage was largely abandoned by the time of Julius Caesar, when a woman remained under her father’s authority by law even when she moved into her husband’s home. This arrangement was one of the factors in the independence Roman women enjoyed relative to those of many other ancient cultures and up to the modern period:[29] although she had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free of his direct scrutiny in her daily life,[30] and her husband had no legal power over her.[31] When her father died, she became legally emancipated (sui iuris).[25] A married woman retained ownership of any property she brought into the marriage.[25] Although it was a point of pride to be a “one-man woman” (univira) who had married only once, there was little stigma attached to divorce, nor to speedy remarriage after the loss of a husband through death or divorce.[32] Under classical Roman law, a husband had no right to abuse his wife physically or compel her to have sex.[33] Wife beating was sufficient grounds for divorce or other legal action against the husband.[34]

Because she remained legally a part of her birth family, a Roman woman kept her own family name for life. Children most often took the father’s name, but in the Imperial period sometimes made their mother’s name part of theirs, or even used it instead.[35] A Roman mother’s right to own property and to dispose of it as she saw fit, including setting the terms of her own will, enhanced her influence over her sons even when they were adults.[36] Because of their legal status as citizens and the degree to which they could become emancipated, women could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business.[37] Some acquired and disposed of sizable fortunes, and are recorded in inscriptions as benefactors in funding major public works.[38]

Roman women could appear in court and argue cases, though it was customary for them to be represented by a man.[39] They were simultaneously disparaged as too ignorant and weak-minded to practice law, and as too active and influential in legal matters—resulting in an edict that limited women to conducting cases on their own behalf instead of others’.[40] Even after this restriction was put in place, there are numerous examples of women taking informed actions in legal matters, including dictating legal strategy to their male advocates.[41]

The first Roman emperor, Augustus, framed his ascent to sole power as a return to traditional morality, and attempted to regulate the conduct of women through moral legislation. Adultery, which had been a private family matter under the Republic, was criminalized,[42] and defined broadly as an illicit sex act (stuprum) that occurred between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband. That is, adouble standard was in place: a married woman could have sex only with her husband, but a married man did not commit adultery when he had sex with a prostitute, slave, or person of marginalized status (infamis).[43] Childbearing was encouraged by the state: the ius trium liberorum (“legal right of three children”) granted symbolic honors and legal privileges to a woman who had given birth to three children, and freed her from any male guardianship.[44]

Stoic philosophies influenced the development of Roman law. Stoics of the Imperial era such as Seneca and Musonius Rufus developed theories ofjust relationships. While not advocating equality in society or under the law, they held that nature gives men and women equal capacity for virtue and equal obligations to act virtuously, and that therefore men and women had an equal need for philosophical education.[21] These philosophical trends among the ruling elite are thought to have helped improve the status of women under the Empire.[45]

Rome had no system of state-supported schooling, and education was available only to those who could pay for it. The daughters of senators and knights seem to have regularly received a primary education (for ages 7 to 12).[46] Regardless of gender, few people were educated beyond that level. Girls from a modest background might be schooled in order to help with the family business or to acquire literacy skills that enabled them to work as scribes and secretaries.[47] The woman who achieved the greatest prominence in the ancient world for her learning was Hypatia of Alexandria, who taught advanced courses to young men and advised the Roman prefect of Egypt on politics. Her influence put her into conflict with the bishop of Alexandria, Cyril, who may have been implicated in her violent death in the year 415 at the hands of a Christian mob.[48]

Roman law recognized rape as a crime in which the victim bore no guilt.[49] Rape was a capital crime.[50] The right to physical integrity was fundamental to the Roman concept of citizenship, as indicated in Roman legend by the rape of Lucretia by the king’s son. After speaking out against the tyranny of the royal family, Lucretia killed herself as a political and moral protest. Roman authors saw her self-sacrifice as the catalyst for overthrowing the monarchy and establishing the republic.[51] As a matter of law, rape could be committed only against a citizen in good standing. The rape of a slave could be prosecuted only as damage to her owner’s property.[52] Most prostitutes in ancient Rome were slaves, though some slaves were protected from forced prostitution by a clause in their sales contract.[53] A free woman who worked as a prostitute or entertainer lost her social standing and became infamis, “disreputable”; by making her body publicly available, she had in effect surrendered her right to be protected from sexual abuse or physical violence.[54] Attitudes toward rape changed as the empire came under Christian rule. St. Augustine and other Church Fathers interpreted Lucretia’s suicide as perhaps an admission that she had encouraged the rapist and experienced pleasure.[55] Under Constantine, the first Christian emperor, if a father accused a man of abducting his daughter, but the daughter had given her consent to an elopement, the couple were both subject to being burnt alive. If she had been raped or abducted against her will, she was still subject to lesser penalties as an accomplice, “on the grounds that she could have saved herself by screaming for help.”[56]

Religious scriptures

Bible

“And Adam called his wife’s name Eve, because she was the mother of all living.” Genesis 3:20)

“Now Deborah, a prophet, the wife of Lappidoth, she judged Israel at that time.” (Judges 4:4) God chose a woman, Deborah, to guide Israel.

“Mary Magdalene went and said to the disciples, “I have seen the Lord”; and she told them that he had said these things to her.” (John 20:18) The first person to see Jesus after his crucifixion was a woman, Mary.

Qur’an

The Qur’an, revealed to Muhammad over the course of 23 years, provided guidance to the Islamic community and modified existing customs in Arab society.[57] From 610 and 661, known as the early reforms under Islam, the Qur’an introduced fundamental reforms to customary law and introduced rights for women in marriage, divorce and inheritance. By providing that the wife, not her family, would receive a dowry from the husband, which she could administer as her personal property, the Qur’an made women a legal party to the marriage contract.[58]

While in customary law inheritance was limited to male descendants, the Qur’an introduced rules on inheritance with certain fixed shares being distributed to designated heirs, first to the nearest female relatives and then the nearest male relatives.[59] According to Annemarie Schimmel “compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work.”[60]

The general improvement of the status of Arab women included prohibition of female infanticide and recognizing women’s full personhood.[61] Women generally gained greater rights than women in pre-Islamic Arabia[62][63] and medieval Europe.[64] Women were not accorded with such legal status in other cultures until centuries later.[65] According to Professor William Montgomery Watt, when seen in such historical context, Muhammad “can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women’s rights.”[66]

The Middle Ages

According to English Common Law, which developed from the 12th century onward, all property which a wife held at the time of a marriage became a possession of her husband. Eventually English courts forbade a husband’s transferring property without the consent of his wife, but he still retained the right to manage it and to receive the money which it produced. French married women suffered from restrictions on their legal capacity which were removed only in 1965.[67] In the 16th century, the Reformation in Europe allowed more women to add their voices, including the English writers Jane Anger, Aemilia Lanyer, and the prophetess Anna Trapnell. English and American Quakers believed that men and women were equal. Many Quaker women were preachers.[68] Despite relatively greater freedom for Anglo-Saxon women, until the mid-19th century, writers largely assumed that a patriarchal order was a natural order that had always existed.[69] This perception was not seriously challenged until the 18th century when Jesuit missionaries found matrilineality in native North American peoples.[70]

18th and 19th century Europe

The Debutante (1807) byHenry Fuseli; The woman, victim of male social conventions, is tied to the wall, made to sew and guarded by governesses. The picture reflects Mary Wollstonecraft‘s views in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792.[71]

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded freedom of religion, the abolition of slavery, rights for women, rights for those who did not own property and universal suffrage.[72] In the late 18th century the question of women’s rights became central to political debates in both France and Britain. At the time some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, who defended democratic principles of equality and challenged notions that a privileged few should rule over the vast majority of the population, believed that these principles should be applied only to their own gender and their own race. The philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau for example thought that it was the order of nature for woman to obey men. He wrote “Women do wrong to complain of the inequality of man-made laws” and claimed that “when she tries to usurp our rights, she is our inferior”.[73]

The efforts of Dorothea von Velen–mistress of Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine–led to the abolition of couverture in the Electoral Palatinate in 1707, making it an early beacon of women’s rights. The Palatinate was the first German state to abolish couverture, but it was briefly re-instated by Karl III Philipp, Johann Wilhelm’s successor. Dorothea protested from exile in Amsterdam. She published her memoirs, A Life for Reform, which were highly critical of Karl III Philipp’s government. To avoid a scandal, Karl III Philipp yielded to Dorothea’s demands, and couverture was once again abolished.[74]

First page of theDeclaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen

In 1791 the French playwright and political activist Olympe de Gouges published the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen,[75] modelled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. The Declaration is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality. It states that: “This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society”. The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of theDeclaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as “almost a parody…of the original document”. The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.” The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied: “Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility”. De Gouges expands the sixth article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which declared the rights of citizens to take part in the formation of law, to:

“All citizens including women are equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their capacity, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents”.

De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights.[76]

Mary Wollstonecraft, a British writer and philosopher, published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, arguing that it was the education and upbringing of women that created limited expectations.[77][78] Wollstonecraft attacked gender oppression, pressing for equal educational opportunities, and demanded “justice!” and “rights to humanity” for all.[79] Wollstonecraft, along with her British contemporaries Damaris Cudworth and Catherine Macaulaystarted to use the language of rights in relation to women, arguing that women should have greater opportunity because like men, they were moral and rational beings.[80]

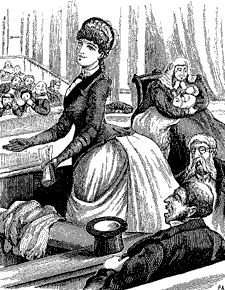

A Punch cartoon from 1867 mocking John Stuart Mill‘s attempt to replace the term ‘man’ with ‘person’, i.e. give women the right to vote. Caption: Mill’s Logic: Or, Franchise for Females. “Pray clear the way, there, for these – a – persons.”[81]

In his 1869 essay The Subjection of Women the English philosopher and political theorist John Stuart Mill described the situation for women in Britain as follows:

“We are continually told that civilization and Christianity have restored to the woman her just rights. Meanwhile the wife is the actual bondservant of her husband; no less so, as far as the legal obligation goes, than slaves commonly so called.”

Then a member of parliament, Mill argued that women deserve the right to vote, though his proposal to replace the term “man” with “person” in the second Reform Bill of 1867was greeted with laughter in the House of Commons and defeated by 76 to 196 votes. His arguments won little support amongst contemporaries[81] but his attempt to amend the reform bill generated greater attention for the issue of women’s suffrage in Britain.[82] Initially only one of several women’s rights campaigns, suffrage became the primary cause of the British women’s movement at the beginning of the 20th century.[83] At the time the ability to vote was restricted to wealthy property ownerswithin British jurisdictions. This arrangement implicitly excluded women as property lawand marriage law gave men ownership rights at marriage or inheritance until the 19th century. Although male suffrage broadened during the century, women were explicitly prohibited from voting nationally and locally in the 1830s by a Reform Act and the Municipal Corporations Act.[84] Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst led the public campaign on women’s suffrage and in 1918 a bill was passed allowing women over the age of 30 to vote.[84]

Equal employment rights for women and men

The rights of women and men to have equal pay and equal benefits for equal work were openly denied by the British Hong Kong Government up to the early 1970s. Leslie Wah-Leung Chung (鍾華亮, 1917–2009), President of the Hong Kong Chinese Civil Servants’ Association 香港政府華員會[85] (1965–68), contributed to the establishment of equal pay for men and women, including the right for married women to be permanent employees. Before this, the job status of a woman changed from permanent employee to temporary employee once she was married, thus losing the pension benefit. Some of them even lost their jobs. Since nurses were mostly women, this improvement of the rights of married women meant much to the Nursing profession.[7][8][86][87][88][89][90][91]

Suffrage, the right to vote

During the 19th century some women began to agitate for the right to vote and participate in government and law making.[92] Other women opposed suffrage like Helen Kendrick Johnson, whose prescient 1897 work Woman and the Republic contains perhaps the best arguments against women’s suffrage of the time.[93] The ideals of women’s suffrage developed alongside that of universal suffrage and today women’s suffrage is considered a right (under theConvention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women). During the 19th century the right to vote was gradually extended in many countries and women started to campaign for their right to vote. In 1893 New Zealand became the first country to give women the right to vote on a national level. Australia gave women the right to vote in 1902.[82] A number of Nordic countries gave women the right to vote in the early 20th century – Finland (1906), Norway (1913), Denmark and Iceland (1915). With the end of the First World War many other countries followed – theNetherlands (1917), Austria, Azerbaijan,[94] Canada, Czechoslovakia, Georgia, Poland and Sweden (1918), Germanyand Luxembourg (1919), and the United States (1920). Spain gave women the right to vote in 1931, France in 1944, Belgium, Italy, Romania andYugoslavia in 1946. Switzerland gave women the right to vote in 1971, and Liechtenstein in 1984.[82]

In Latin America some countries gave women the right to vote in the first half of the 20th century – Ecuador (1929), Brazil (1932), El Salvador (1939),Dominican Republic (1942), Guatemala (1956) and Argentina (1946). In India, under colonial rule, universal suffrage was granted in 1935. Other Asian countries gave women the right to vote in the mid 20th century – Japan (1945), China (1947) and Indonesia (1955). In Africa, women generally got the right to vote along with men through universal suffrage – Liberia (1947), Uganda (1958) and Nigeria (1960). In many countries in the Middle East universal suffrage was acquired after the Second World War, although in others, such as Kuwait, suffrage is very limited.[82] On 16 May 2005, the Parliament of Kuwait extended suffrage to women by a 35–23 vote.[95]

Property rights

During the 19th century some women in the United States and Britain began to challenge laws that denied them the right to their property once they married. Under the common law doctrine of coverture husbands gained control of their wives’ real estate and wages. Beginning in the 1840s, state legislatures in the United States[96] and the British Parliament[97] began passing statutes that protected women’s property from their husbands and their husbands’ creditors. These laws were known as the Married Women’s Property Acts.[98] Courts in the 19th-century United States also continued to require privy examinations of married women who sold their property. A privy examination was a practice in which a married woman who wished to sell her property had to be separately examined by a judge or justice of the peace outside of the presence of her husband and asked if her husband was pressuring her into signing the document.[99]

Modern movements

|

|

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article and discuss the issue on the talk page. (December 2010) |

Iraqi-American writer and activist Zainab Salbi, the founder of Women for Women International.

In the subsequent decades women’s rights again became an important issue in the English speaking world. By the 1960s the movement was called “feminism” or “women’s liberation.” Reformers wanted the same pay as men, equal rights in law, and the freedom to plan their families or not have children at all. Their efforts were met with mixed results.[100]

In the UK, a public groundswell of opinion in favour of legal equality had gained pace, partly through the extensive employment of women in what were traditional male roles during both world wars. By the 1960s the legislative process was being readied, tracing through MP Willie Hamilton‘s select committee report, his equal pay for equal work bill,[101] the creation of a Sex Discrimination Board, Lady Sear‘s draft sex anti-discrimination bill, a government Green Paper of 1973, until 1975 when the first British Sex Discrimination Act, an Equal Pay Act, and an Equal Opportunities Commissioncame into force.[102][103] With encouragement from the UK government, the other countries of the EEC soon followed suit with an agreement to ensure that discrimination laws would be phased out across the European Community.

In the USA, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was created in 1966 with the purpose of bringing about equality for all women. NOW was one important group that fought for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). This amendment stated that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex.”[104] But there was disagreement on how the proposed amendment would be understood. Supporters believed it would guarantee women equal treatment. But critics feared it might deny women the right be financially supported by their husbands. The amendment died in 1982 because not enough states had ratified it. ERAs have been included in subsequent Congresses, but have still failed to be ratified.[105]

In Ukraine, FEMEN was founded in 2008. The organisation is internationally known for its topless protests against sex tourists, international marriage agencies, sexism and other social, national and international social illnesses. FEMEN has sympathisers groups in many European countries through social media.

Birth control and reproductive rights

In the 1870s feminists advanced the concept of voluntary motherhood as a political critique of involuntary motherhood[106] and expressing a desire for women’s emancipation.[107] Advocates for voluntary motherhood disapproved of contraception, arguing that women should only engage in sex for the purpose of procreation[108] and advocated for periodic or permanent abstinence.[109]

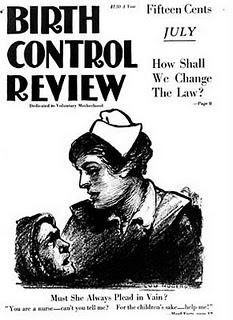

Cover of the 1919 Birth Control Review, published by Margaret Sanger. In relation to “How shall we change the law?” Sanger wrote “…women appeal in vain for instruction concerning contraceptives. Physicians are willing to perform abortions where they are pronounced necessary, but they refuse to direct the use of preventives which would make the abortions unnecessary… “I can’t do it – the law does not permit it.””[110]

In the early 20th century birth control was advanced as alternative to the then fashionable termsfamily limitation and voluntary motherhood.[111][112] The phrase “birth control” entered the English language in 1914 and was popularised by Margaret Sanger,[111][112] who was mainly active in the US but had gained an international reputation by the 1930s. The British birth control campaigner Marie Stopes made contraception acceptable in Britain during the 1920 by framing it in scientific terms. Stopes assisted emerging birth control movements in a number of British colonies.[113] The birth control movement advocated for contraception so as to permit sexual intercourse as desired without the risk of pregnancy.[109] By emphasizing control the birth control movement argued that women should have control over their reproduction, and the movement came to have close ties to the feminist movement. Slogans such as “control over our own bodies” criticised male domination and demanded women’s liberation, a connotation that is absent from the family planning, population control and eugenics movements.[114] In the 1960s and 1970s the birth control movement advocated for the legalisation of abortion and large scale education campaigns about contraception by governments.[115] In the 1980s birth control and population control organisations co-operated in demanding rights to contraception and abortion, with an increasing emphasis on “choice”.[114]

Birth control has become a major theme in United States politics. Reproductive issues are cited as examples of women’s powerlessness to exercise their rights.[116] The societal acceptance of birth control required the separation of sex from procreation, making birth control a highly controversial subject in the 20th century.[115] In the United States birth control has become an arena for conflict between liberal and conservative values, raising questions about family, personal freedom, state intervention, religion in politics, sexual morality and social welfare.[116]Reproductive rights, that is rights relating to sexual reproduction and reproductive health,[117] were first discussed as a subset of human rights at the United Nation’s 1968 International Conference on Human Rights.[118] Reproductive rights are not recognised in international human rights lawand is an umbrella term that may include some or all of the following rights: the right to legal or safe abortion, the right to control one’s reproductive functions, the right to access quality reproductive healthcare, and the right to education and access in order to make reproductive choices free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.[119] Reproductive rights may also be understood to include education about contraception andsexually transmitted infections, and freedom from coerced sterilization and contraception, protection from gender-based practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and male genital mutilation (MGM).[117][118][119][120] Reproductive rights are understood as rights of both men and women, but are most frequently advanced as women’s rights.[118]

Women’s access to legal abortion is restricted by law in most countries in the world.[121] Where abortion is permitted by law, women may only have limited access to safe abortion services. Some countries still prohibit abortion in all cases, but in many countries and jurisdictions, abortion is permitted to save the pregnant woman’s life, or if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest.[122] According to Human Rights Watch, “Abortion is a highly emotional subject and one that excites deeply held opinions. However, equitable access to safe abortion services is first and foremost a human right. Where abortion is safe and legal, no one is forced to have one. Where abortion is illegal and unsafe, women are forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term or suffer serious health consequences and even death. Approximately 13% of maternal deaths worldwide are attributable to unsafe abortion—between 68,000 and 78,000 deaths annually.”[122] According to Human Rights Watch, “the denial of a pregnant woman’s right to make an independent decision regarding abortion violates or poses a threat to a wide range of human rights.”[123][124] Other groups however, such as the Catholic Church, the Christian right and most Orthodox Jews, regard abortion not as a right but as a ‘moral evil’.[125]

United Nations and World Conferences on Women

In 1946 the United Nations established a Commission on the Status of Women.[126][127] Originally as the Section on the Status of Women, Human Rights Division, Department of Social Affairs, and now part of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Since 1975 the UN has held a series of world conferences on women’s issues, starting with the World Conference of the International Women’s Year in Mexico City. These conferences created an international forum for women’s rights, but also illustrated divisions between women of different cultures and the difficulties of attempting to apply principles universally.[128] Four World Conferences have been held, the first in Mexico City (International Women’s Year, 1975), the second inCopenhagen (1980) and the third in Nairobi (1985). At the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995), The Platform for Action was signed. This included a commitment to achieve “gender equality and the empowerment of women”.[129][130] In 2010, UN Women is founded by merging of Division for the Advancement of Women, International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women, Office of the Special Adviser or Gender Issues Advancement of Women and United Nations Development Fund for Women by General Assembly Resolution 63/311.

Natural law and women’s rights

17th century natural law philosophers in Britain and America, such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Locke, developed the theory of natural rights in reference to ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and the Christian theologist Aquinas. Like the ancient philosophers, 17th century natural law philosophers defended slavery and an inferior status of women in law.[131] Relying on ancient Greek philosophers, natural law philosophers argued that natural rights were not derived from god, but were “universal, self-evident, and intuitive”, a law that could be found in nature. They believed that natural rights were self-evident to “civilised man” who lives “in the highest form of society”.[132] Natural rights derived from human nature, a concept first established by the ancient Greek philosopher Zeno of Citium in Concerning Human Nature. Zenon argued that each rational and civilized male Greek citizen had a “divine spark” or “soul” within him that existed independent of the body. Zeno founded the Stoic philosophy and the idea of a human nature was adopted by other Greek philosophers, and later natural law philosophers and western humanists.[133] Aristotle developed the widely adopted idea of rationality, arguing that man was a “rational animal” and as such a natural power of reason. Concepts of human nature in ancient Greece depended on gender, ethnic, and other qualifications[134] and 17th century natural law philosophers came to regard women along with children, slaves and non-whites, as neither “rational” nor “civilised”.[132] Natural law philosophers claimed the inferior status of women was “common sense” and a matter of “nature”. They believed that women could not be treated as equal due to their “inner nature”.[131] The views of 17th century natural law philosophers were opposed in the 18th and 19th century byevangelical natural theology philosophers such as William Wilberforce and Charles Spurgeon, who argued for the abolition of slavery and advocated for women to have rights equal to that of men.[131] Modern natural law theorist, and advocates of natural rights, claim that all people have a human nature, regardless of gender, ethnicity or other qualifications, therefore all people have natural rights.[134]

Human rights and women’s rights

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, enshrines “the equal rights of men and women”, and addressed both the equality and equity issues.[135] In 1979 the United Nations General Assemblyadopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) for legal implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it came into force on 3 September 1981. The UN member states that have not ratified the convention are Iran, Nauru, Palau, Somalia, Sudan, Tonga, and the United States. Niueand the Vatican City, which are non-member states, have also not ratified it.[136]

The Convention defines discrimination against women in the following terms:

Any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.

It also establishes an agenda of action for putting an end to sex-based discrimination for which states ratifying the Convention are required to enshrine gender equality into their domestic legislation, repeal all discriminatory provisions in their laws, and enact new provisions to guard against discrimination against women. They must also establish tribunals and public institutions to guarantee women effective protection against discrimination, and take steps to eliminate all forms of discrimination practiced against women by individuals, organizations, and enterprises.[137]

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325

On 31 October 2000, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, the first formal and legal document from the United Nations Security Council that requires all states respect fully international humanitarian law and international human rights law appicable to the rights and protection of women and girls during and after the armed conflicts.

Hillary Rodham Clinton speaks out for women’s rights

During the eight years that Ms. Clinton was First Lady of the United States (1993–2001), she traveled to 79 countries around the world.[138] A March 1995 five-nation trip to South Asia, on behest of the U.S. State Department and without her husband, sought to improve relations with Indiaand Pakistan. Clinton was troubled by the plight of women she encountered, but found a warm response from the people of the countries she visited and a gained better relationship with the American press corps.[139] The trip was a transformative experience for her and presaged her eventual career in diplomacy.[140] In a September 1995 speech before the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, Clinton argued very forcefully against practices that abused women around the world and in the People’s Republic of China itself,[141] declaring “that it is no longer acceptable to discuss women’s rights as separate from human rights”.[141] Delegates from over 180 countries heard her say: “If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.”[142] In doing so, she resisted both internal administration and Chinese pressure to soften her remarks.[138][142] She was one of the most prominent international figures during the late 1990s to speak out against the treatment of Afghan women by the Islamist fundamentalistTaliban.[143][144] She helped create Vital Voices, an international initiative sponsored by the United States to promote the participation of women in the political processes of their countries.[145] It and Clinton’s own visits encouraged women to make themselves heard in the Northern Ireland peace process.[146]

Maputo Protocol

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol, was adopted by the African Union on 11 July 2003 at its second summit in Maputo,[147] Mozambique. On 25 November 2005, having been ratified by the required 15 member nations of the African Union, the protocol entered into force.[148] The protocol guarantees comprehensive rights to women including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, and to control of theirreproductive health, and an end to female genital mutilation.[149]

Rape and sexual violence

A young ethnic Chinese woman who was in one of the Imperial Japanese Army‘s “comfort battalions” is interviewed by anAllied officer (see Comfort Women).

Rape, sometimes called sexual assault, is an assault by a person involving sexual intercourse with or sexual penetration of another person without that person’s consent. Rape is generally considered a serious sex crime as well as a civil assault. When part of a widespread and systematic practice rape and sexual slavery are now recognised as crime against humanity and war crime. Rape is also now recognised as an element of the crime ofgenocide when committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a targeted group.

Rape as an element of the crime of genocide

In 1998, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda established by the United Nations made landmark decisions that rape is a crime of genocideunder international law. The trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the mayor of Taba Commune in Rwanda, established precedents that rape is an element of the crime of genocide. The Akayesu judgement includes the first interpretation and application by an international court of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The Trial Chamber held that rape, which it defined as “a physical invasion of a sexual nature committed on a person under circumstances which are coercive”, and sexual assault constitute acts of genocide insofar as they were committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a targeted group, as such. It found that sexual assault formed an integral part of the process of destroying theTutsi ethnic group and that the rape was systematic and had been perpetrated against Tutsi women only, manifesting the specific intent required for those acts to constitute genocide.[150]

Judge Navanethem Pillay said in a statement after the verdict: “From time immemorial, rape has been regarded as spoils of war. Now it will be considered a war crime. We want to send out a strong message that rape is no longer a trophy of war.”[151] An estimated 500,000 women were raped during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.[152]

Rape and sexual enslavement as crime against humanity

The Rome Statute Explanatory Memorandum, which defines the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, recognises rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy,enforced sterilization, “or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity” as crime against humanity if the action is part of a widespread or systematic practice.[153][154] TheVienna Declaration and Programme of Action also condemn systematic rape as well as murder, sexual slavery, and forced pregnancy, as the “violations of the fundamental principles of international human rights and humanitarian law.” and require a particularly effective response.[155]

Rape was first recognised as crime against humanity when the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia issued arrest warrants based on the Geneva Conventions and Violations of the Laws or Customs of War. Specifically, it was recognised that Muslim women in Foca (southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina) were subjected to systematic and widespread gang rape, torture and sexual enslavement by Bosnian Serb soldiers, policemen, and members of paramilitary groups after the takeover of the city in April 1992.[156] The indictment was of major legal significance and was the first time that sexual assaults were investigated for the purpose of prosecution under the rubric of torture and enslavement as a crime against humanity.[156] The indictment was confirmed by a 2001 verdict by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia that rape and sexual enslavement are crimes against humanity. This ruling challenged the widespread acceptance of rape and sexual enslavement of women as intrinsic part of war.[157] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia found three Bosnian Serb men guilty of rape of Bosniac (Bosnian Muslim) women and girls (some as young as 12 and 15 years of age), in Foca, eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. Furthermore two of the men were found guilty of the crime against humanity of sexual enslavement for holding women and girls captive in a number of de facto detention centres. Many of the women subsequently disappeared.[157]

2011 study of status by country

Status of women by country according to data collected by Lauren Streib

In the 26 September 2011 issue of Newsweek magazine[158] a study was published on the rights and quality of life of women in countries around the world. The factors taken into account were legal justice, health and healthcare, education, economic opportunity, and political power. The rankings were determined by Lauren Streib by uniform criteria and available statistics.[159] According to the study, the best and worst were:[160]

| Rank | Country | Overall | Justice | Health | Education | Economics | Politics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 90.5 | 96.7 | 88.0 | 92.8 | |

| 2 | 99.2 | 90.8 | 94.8 | 95.5 | 90.3 | 93.1 | |

| 3 | 96.6 | 100.0 | 92.7 | 92.0 | 91.0 | 66.9 | |

| 4 | 95.3 | 86.1 | 94.9 | 97.6 | 88.5 | 78.4 | |

| 5 | 92.8 | 80.2 | 91.4 | 91.3 | 86.8 | 100.0 | |

| 6 | 91.9 | 87.9 | 94.4 | 97.3 | 82.6 | 74.6 | |

| 7 | 91.3 | 79.3 | 100.0 | 74.0 | 93.5 | 93.9 | |

| 8 | 89.8 | 82.9 | 92.8 | 97.3 | 83.9 | 68.6 | |

| 9 | 88.2 | 80.7 | 93.3 | 93.9 | 85.3 | 65.1 | |

| 10 | 87.7 | 74.0 | 95.0 | 99.0 | 83.0 | 68.4 |

| Rank | Country | Overall | Justice | Health | Education | Economics | Politics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 165 | 0.0 | 20.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 70.9 | 22.2 | |

| 164 | 2.0 | 8.4 | 2.0 | 41.1 | 55.3 | 16.6 | |

| 163 | 12.1 | 36.2 | 44.4 | 34.1 | 48.8 | 0.0 | |

| 162 | 13.6 | 6.5 | 11.4 | 45.1 | 67.8 | 27.2 | |

| 160 | 17.6 | 22.7 | 29.9 | 25.8 | 64.3 | 49.8 | |

| 160 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 53.6 | 86.5 | 46.0 | 1.9 | |

| 159 | 21.2 | 26.5 | 32.9 | 47.5 | 58.6 | 31.3 | |

| 158 | 21.4 | 49.7 | 49.6 | 34.0 | 50.7 | 19.3 | |

| 157 | 23.7 | 18.6 | 27.2 | 29.9 | 79.7 | 37.4 | |

| 156 | 26.1 | 21.1 | 29.4 | 70.6 | 54.5 | 40.8 |

See also

- Female education

- Gender apartheid

- History of feminism

- Index of feminism articles

- Legal rights of women in history

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of feminists

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women’s rights activists

- List of women’s rights organizations

- Men’s rights

- Pregnant patients’ rights

- Sex workers’ rights

- Timeline of women’s suffrage

- Timeline of women’s rights (other than voting)

- UN Women

- Women’s Property Rights

- Women’s Social and Political Union

References

- Jump up^ Hosken, Fran P., ‘Towards a Definition of Women’s Rights’ in Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2. (May, 1981), pp. 1–10.

- Jump up^ Lockwood, Bert B. (ed.), Women’s Rights: A “Human Rights Quarterly” Reader (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), ISBN 978-0-8018-8374-3.

- Jump up^ http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/12/where-masturbation-and-homosexuality-do-not-exist/265849/

- Jump up^ http://www.amazon.com/Inasmuch-Mary-H-Fulton/dp/1140341804

- Jump up^http://www.hkbu.edu.hk/~libimage/theses/abstracts/b15564174a.pdf

- Jump up^ http://www.cqvip.com/qk/83891A/200203/6479902.html

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rebecca Chan Chung, Deborah Chung and Cecilia Ng Wong, “Piloted to Serve”, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b https://www.facebook.com/PilotedToServe

- Jump up^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 1995, Part 2. Harvard University Press. p. 114.ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Jump up^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- Jump up^ Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 1995, Part 2. Harvard University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Jump up^ Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-631-23394-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddess, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1975. pp. 60–62.

- Jump up^ Tierney, Helen (1999). Women’s studies encyclopaedia, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 609–610.ISBN 978-0-313-31072-0.

- Jump up^ Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 137 [1]

- Jump up^ Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 134 [2]

- Jump up^ Pomeroy 2002, p. 34

- Jump up^ Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-631-23394-7.

- Jump up^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Colish, Marcia L. (1990). The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: Stoicism in classical Latin literature. BRILL. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-90-04-09327-0.

- Jump up^ Fulvia was the first historical woman to appear on coins:goddesses and personifications appeared widely.

- Jump up^ A.N. Sherwin-White, Roman Citizenship (Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 211 and 268; Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 31–32, 457, et passim.

- Jump up^ Walter Eck, “The Emperor and His Advisors,” Cambridge Ancient History (Cambridge University History, 2000), p. 211.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, pp. 19–20.

- Jump up^ David Johnston, Roman Law in Context (Cambridge University Press, 1999), chapter 3.3; Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, Chapter IV; Yan Thomas, “The Division of the Sexes in Roman Law,” in A History of Women from Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints(Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 134.

- Jump up^ Martha C. Nussbaum, “The Incomplete Feminism of Musonius Rufus, Platonist, Stoic, and Roman,” in The Sleep of Reason: Erotic Experience and Sexual Ethics in Ancient Greece and Rome (University of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 300; Sabine MacCormack, “Sin, Citizenship, and the Salvation of Souls: The Impact of Christian Priorities on Late-Roman and Post-Roman Society,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 39.4 (1997), p. 651.

- Jump up^ Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, p. 20.

- Jump up^ Eva Cantarella, Pandora’s Daughters: The Role and Status of Women in Greek and Roman Antiquity (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), pp. 140–141; J.P. Sullivan, “Martial’s Sexual Attitudes,” Philologus 123 (1979), p. 296, specifically on sexual freedom.

- Jump up^ Beryl Rawson, “The Roman Family,” in The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives (Cornell University Press, 1986), p. 15.

- Jump up^ Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, pp. 19–20, 22.

- Jump up^ Susan Treggiari, Roman Marriage: Iusti Coniuges from the Time of Cicero to the Time of Ulpian (Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 258–259, 500–502 et passim.

- Jump up^ Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, p. 95.

- Jump up^ Garrett G. Fagan, “Violence in Roman Social Relations,” inThe Oxford Handbook of Social Relations (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 487.

- Jump up^ Rawson, “The Roman Family,” p. 18.

- Jump up^ Severy, Augustus and the Family, p. 12.

- Jump up^ Frier and McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law, p. 461; W.V. Harris, “Trade,” in The Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire A.D. 70–192 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), vol. 11, p. 733.

- Jump up^ Margaret L. Woodhull, “Matronly Patrons in the Early Roman Empire: The Case of Salvia Postuma,” in Women’s Influence on Classical Civilization (Routledge, 2004), p. 77.

- Jump up^ Richard A. Bauman, Women and Politics in Ancient Rome(Routledge, 1992, 1994), p. 50.

- Jump up^ Bauman, Women and Politics, pp. 50–51; Juvenal, Satire6, on women busy in the courts.

- Jump up^ Bauman, Women and Politics, pp. 51–52.

- Jump up^ Beth Severy, Augustus and the Family at the Birth of the Empire (Routledge, 2002; Taylor & Francis, 2004), p. 4.

- Jump up^ Thomas McGinn, “Concubinage and the Lex Iulia on Adultery,” Transactions of the American Philological Association 121 (1991), p. 342; Nussbaum, “The Incomplete Feminism of Musonius Rufus,” p. 305, noting that custom “allowed much latitude for personal negotiation and gradual social change”; Elaine Fantham, “Stuprum: Public Attitudes and Penalties for Sexual Offences in Republican Rome,” inRoman Readings: Roman Response to Greek Literature from Plautus to Statius and Quintilian (Walter de Gruyter, 2011), p. 124, citing Papinian, De adulteriis I and Modestinus,Liber Regularum I. Eva Cantarella, Bisexuality in the Ancient World (Yale University Press, 1992, 2002, originally published 1988 in Italian), p. 104; Catherine Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 34–35.

- Jump up^ Yan Thomas, “The Division of the Sexes in Roman Law,” inA History of Women from Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints (Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 133.

- Jump up^ Ratnapala, Suri (2009). Jurisprudence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-521-61483-2.

- Jump up^ Marietta Horster, “Primary Education,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 90.

- Jump up^ Beryl Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy(Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 80.

- Jump up^ Teresa Morgan, “Education,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 20.

- Jump up^ Ariadne Staples, From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion (Routledge, 1998), pp. 81–82; Jane F. Gardner, Women in Roman Law and Society(Indiana University Press, 1991), pp. 118ff. Roman law also recognized rape committed against males.

- Jump up^ Amy Richlin, “Not before Homosexuality: The Materiality of the cinaedus and the Roman Law against Love between Men,”Journal of the History of Sexuality 3.4 (1993), pp. 562–563.

- Jump up^ Ann L. Kuttner, “Culture and History at Pompey’s Museum,”Transactions of the American Philological Association 129 (1999), p. 348; Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price,Religions of Rome: A History (Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 1, pp. 1–10, as cited and elaborated by Phyllis Culham, “Women in the Roman Republic,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 158.

- Jump up^ Under the Lex Aquilia; Thomas A.J. McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law in Ancient Rome (Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 314; Gardner, Women in Roman Law and Society, p. 119.

- Jump up^ McGinn, McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law, pp. 288ff.

- Jump up^ Gardner, Women in Roman Law and Society, p. 119; McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law in Ancient Rome, p. 326.

- Jump up^ Staples, From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins, p. 164, citing Norman Bryson, “Two Narratives of Rape in the Visual Arts: Lucretia and the Sabine Women,” in Rape (Blackwell, 1986), p. 199. Augustine’s interpretation of the rape of Lucretia (in City of God 1.19) has generated a substantial body of criticism, starting with Machiavelli‘s satire. InAugustine of Hippo: A Biography (Faber, 1967), Peter Browncharacterized this section of Augustine’s work as his most vituperative attack on Roman ideals of virtue. See also Carol J. Adams and Marie M. Fortune, Violence against Women and Children: A Christian Theological Sourcebook (Continuum, 1995), pp. 219ff.; Melissa M. Matthes, The Rape of Lucretia and the Founding of Republics (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), pp. 68ff. (also on Machiavelli); Virginia Burrus,Saving Shame: Martyrs, Saints, and Other Abject Subjects(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), pp. 125ff.; Amy Greenstadt, Rape and the Rise of the Author: Gendering Intention in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2009), p. 71; Melissa E. Sanchez, Erotic Subjects: The Sexuality of Politics in Early Modern English Literature (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 93ff.

- Jump up^ Gardner, Women in Roman Law and Society, p. 120; James A. Brundage, Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe (University of Chicago Press, 1987, 1990), p. 107; Charles Matson Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire (Routledge, 2004), p. 179; Timothy David Barnes,Constantine and Eusebius (Harvard University Press, 1981), p. 220; Gillian Clark, Women in Late Antiquity: Pagan and Christian Lifestyles (Oxford University Press, 1993), pp. 36–37, characterizing Constantine’s law as “unusually dramatic even for him.”

- Jump up^ Esposito, John L., with DeLong-Bas, Natana J. (2001).Women in Muslim Family Law, 2nd revised Ed. Available here via GoogleBooks preview. Syracuse University Press.ISBN 0-8156-2908-7 (pbk); p. 3.

- Jump up^ Esposito (with DeLong-Bas) 2001, p. 4.

- Jump up^ Esposito (with DeLong-Bas) 2001, pp. 4–5.

- Jump up^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam. SUNY Press. p. 65.ISBN 978-0-7914-1327-2.

- Jump up^ Esposito (2004), p. 339.

- Jump up^ John Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path p. 79.

- Jump up^ Majid Khadduri, Marriage in Islamic Law: The Modernist Viewpoints, American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 213–218.

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia of religion, second edition, Lindsay Jones, p. 6224, ISBN 978-0-02-865742-4.

- Jump up^ Lindsay Jones, p. 6224.

- Jump up^ “Interview with Prof William Montgomery Watt”. Alastairmcintosh.com. 27 May 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Badr, Gamal M.; Mayer, Ann Elizabeth (Winter 1984). “Islamic Criminal Justice”. The American Journal of Comparative Law (American Society of Comparative Law) 32(1): 167–169. doi:10.2307/840274. JSTOR 840274

- Jump up^ W. J. Rorabaugh, Donald T. Critchlow, Paula C. Baker (2004). “America’s promise: a concise history of the United States“. Rowman & Littlefield. p.75. ISBN 978-0-7425-1189-7.

- Jump up^ Maine, Henry Sumner. Ancient Law 1861.

- Jump up^ Lafitau, Joseph François, cited by Campbell, Joseph in, Myth, religion, and mother-right: selected writings of JJ Bachofen. Manheim, R (trans.) Princeton, N.J. 1967 introduction xxxiii

- Jump up^ Tomory, Peter. The Life and Art of Henry Fuseli. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972; p. 217. LCCN 72-77546.

- Jump up^ Sweet, William (2003). Philosophical theory and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. University of Ottawa Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7766-0558-6.

- Jump up^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 29 & 30. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- Jump up^ Langdon-Davies, John (1962). Carlos: The Bewitched. Jonathan Cape. pp. 167-170

- Jump up^ Macdonald and Scherf, “Introduction”, pp. 11–12.

- Jump up^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- Jump up^ Brody, Miriam. Mary Wollstonecraft: Sexuality and women’s rights (1759–1797), in Spender, Dale (ed.) Feminist theorists: Three centuries of key women thinkers, Pantheon 1983, pp. 40–59 ISBN 0-394-53438-7.

- Jump up^ Walters, Margaret, Feminism: A very short introduction(Oxford, 2005), ISBN 978-0-19-280510-2.

- Jump up^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- Jump up^ Sweet, William (2003). Philosophical theory and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. University of Ottawa Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7766-0558-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Brave new world – Women’s rights”. National Archives. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Women’s Suffrage”. Scholastic. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- Jump up^ Van Wingerden, Sophia A. (1999). The women’s suffrage movement in Britain, 1866–1928. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-312-21853-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Phillips, Melanie, The Ascent of Woman: A History of the Suffragette Movement (Abacus, 2004)

- Jump up^ http://www.hkccsa.org/

- Jump up^ http://m.torontosun.com/2012/04/06/celebrating-two-lives-well-lived

- Jump up^ http://www.ottawasun.com/videos/celebrating-two-lives-well-lived/1550780688001

- Jump up^ http://www.torontosun.com/2012/04/07/life-love-and-service-recalled

- Jump up^ http://news.singtao.ca/toronto/2012-04-08/city1333873203d3799095.html

- Jump up^ http://epapertor.worldjournal.com/showtor.html?apJi+mgEEOB3Bg1Fmi3TsQ==,MMV3f+xDb0CKYCyOu+WesQ==

- Jump up^ http://www.mingpaotor.com/htm/News/20120408/tfc1.htm

- Jump up^ Krolokke, Charlotte and Anne Scott Sorensen, ‘From Suffragettes to Grrls’ in Gender Communication Theories and Analyses:From Silence to Performance (Sage, 2005).

- Jump up^ Johnson, Helen Kendrick. Woman and the Republic. 1897.

- Jump up^ Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press, 1995.ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3 and Reinhard Schulze. A Modern History of the Islamic World. I.B.Tauris, 2000. ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9.

- Jump up^ “”Kuwait grants women right to vote” CNN.com (May 16, 2005)”. CNN. 16 May 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Married Women’s Property Act | 1848 | New York State”. Womenshistory.about.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Property Rights Of Women”. Umd.umich.edu. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Married Women’s Property Acts (United States [1839]) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia”. Britannica.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Project MUSE – Journal of Women’s History – Married Women’s Property and Male Coercion: United States Courts and the Privy Examination, 1864–1887”. Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Waves of Feminism”. Jofreeman.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Tributes paid to veteran anti-royalist”. BBC News. 27 January 2000.

- Jump up^ The Guardian, 29 December 1975.

- Jump up^ The Times, 29 December 1975 “Sex discrimination in advertising banned”.

- Jump up^ “The National Organization for Women’s 1966 Statement of Purpose”. Now.org. 29 October 1966. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “National Organization for Women: Definition and Much More from”. Answers.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- Jump up^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- Jump up^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- Jump up^ Sanger, Margaret (July 1919). “How Shall we Change the Law”. Birth Control Review (3): 8–9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilkinson Meyer, Jimmy Elaine (2004). Any friend of the movement: networking for birth control, 1920–1940. Ohio State University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8142-0954-7.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Galvin, Rachel. “Margaret Sanger’s “Deeds of Terrible Virtue””. National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Jump up^ Blue, Gregory; , Bunton, Martin P. & Croizier, Ralph C. (2002). Colonialism and the modern worls: selected studies. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-7656-0772-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 978-0-252-02764-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cook, Rebecca J.; Mahmoud F. Fathalla (September 1996). “Advancing Reproductive Rights Beyond Cairo and Beijing”. International Family Planning Perspectives(Guttmacher Institute) 22 (3): 115–121.doi:10.2307/2950752. JSTOR 2950752.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Freedman, Lynn P.; Stephen L. Isaacs (January – February 1993). “Human Rights and Reproductive Choice”.Studies in Family Planning (Population Council) 24 (1): 18–30. doi:10.2307/2939211. JSTOR 2939211.PMID 8475521.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Amnesty International USA (2007). “Stop Violence Against Women: Reproductive rights”. SVAW. Amnesty International USA. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- Jump up^ “Template”. Nocirc.org. 10 December 1993. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Anika Rahman, Laura Katzive and Stanley K. Henshaw. A Global Review of Laws on Induced Abortion, 1985–1997, International Family Planning Perspectives (Volume 24, Number 2, June 1998).

- ^ Jump up to:a bhttp://web.archive.org/web/20081112153841/http://www.hrw.org/women/abortion.html

- Jump up^ “Q&A: Human Rights Law and Access to Abortion”. Hrw.org. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ “Q&A: Human Rights Law and Access to Abortion”. Hrw.org. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 2271.

- Jump up^ “UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Division for the Advancement of Women”.

- Jump up^ “Short History of the Commission on the Status of Women” (PDF).

- Jump up^ Catagay, N., Grown, C. and Santiago, A. 1986. “The Nairobi Women’s Conference: Toward a Global Feminism?” Feminist Studies, 12, 2:401–412.

- Jump up^ “Fourth World Conference on Women. Beijing, China. September 1995. Action for Equality, Development and Peace”.

- Jump up^ United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women: Introduction

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-60957-143-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-60957-143-6.

- Jump up^ Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-60957-143-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-60957-143-6.

- Jump up^ “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”.

- Jump up^ “Microsoft Word — IV-8.en.doc” (PDF). Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Article 2 (e).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Healy, Patrick (December 26, 2007). “The Résumé Factor: Those 8 Years as First Lady”. The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- Jump up^ Gerth and Van Natta Jr. 2007, pp. 149–151.

- Jump up^ Klein, Joe (November 5, 2009). “The State of Hillary: A Mixed Record on the Job”. Time. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Tyler, Patrick (September 6, 1995). “Hillary Clinton, In China, Details Abuse of Women”. The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lemmon, Gayle Tzemach (March 6, 2011). “The Hillary Doctrine”. Newsweek. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Jump up^ Rashid, Ahmed (2002). Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-830-4. pp. 70, 182.

- Jump up^ “Feminist Majority Joins European Parliament’s Call to End Gender Apartheid in Afghanistan”. Feminist Majority. Spring 1998. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- Jump up^ “Vital Voices – Our History”. Vital Voices. 2000. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- Jump up^ Dobbs, Michael (January 10, 2008). “Clinton and Northern Ireland”. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ African Union: Rights of Women Protocol Adopted, press release, Amnesty International, 22 July 2003.

- Jump up^ UNICEF: toward ending female genital mutilation, press release, UNICEF, 7 February 2006.

- Jump up^ The Maputo Protocol of the African Union, brochure produced by GTZ for the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

- Jump up^ Fourth Annual Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to the General Assembly (September, 1999), accessed at [3].

- Jump up^ Navanethem Pillay is quoted by Professor Paul Walters in his presentation of her honorary doctorate of law, Rhodes University, April 2005 [4]

- Jump up^ Violence Against Women: Worldwide Statistics[dead link]

- Jump up^ As quoted by Guy Horton in Dying Alive – A Legal Assessment of Human Rights Violations in Burma April 2005, co-Funded by The Netherlands Ministry for Development Co-Operation. See section “12.52 Crimes against humanity”, Page 201. He references RSICC/C, Vol. 1 p. 360.

- Jump up^ “Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court”. United Nations. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- Jump up^ Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, Section II, paragraph 38.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rape as a Crime Against Humanity[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bosnia and Herzegovina : Foca verdict – rape and sexual enslavement are crimes against humanity. 22 February 2001. Amnesty International.

- Jump up^ Streib, Lauren (26 September 2011). “The Best and World Places to be a Woman”. Newsweek. pp. 30–33

- Jump up^ Streib, Lauren. “The Best and Worst Places for Women”. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Jump up^ Streib, Lauren. “The Best and Worst Places for Women”. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

Sources

- Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 2.. Harvard University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513067-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women’s rights. |

Categories: Women, Women In islam, Women Rights, Women's right

Thank you Dr. Zia sahib

Jazakumullah.

Mirza Ahmad