A statue of Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī in Uzbekistan. The Muslim Times has the best collection for the Muslim heritage, religion and science correlation and about the holy Quran

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

There are about 750 verses in Quran urging Muslims to make use of reason to understand nature and thus reach their understanding of the Creator, in contrast to just 250 verses about legislation. The Holy Quran states:

In the creation of the heavens and the earth and in the alternation of the night and the day there are indeed Signs for men of understanding; those who remember Allah while standing, sitting, and lying on their sides, and ponder over the creation of the heavens and the earth: ‘Our Lord, Thou hast not created this in vain or without purpose.’ (Al Quran 3:191-192)

The Quran not only encouraged Muslims to study nature and acquire secular knowledge but also provided specific information on several occasions. For example the Holy Quran states about computing:

And We have made the night and the day two Signs, and the Sign of night We have made dark, and the Sign of day We have made sightgiving, that you may seek bounty from your Lord, and that you may know the computation of years and the science of reckoning and mathematics. And everything We have explained with a detailed explanation. (Al Quran 17:13)

No wonder the early Muslim scientists made great strides in the rapidly emerging fields of astronomy and mathematics. In Sura Yunus the Holy Quran states:

He it is Who made the sun radiate a brilliant light and the moon reflect a lustre, and ordained for it stages, that you might know the number of years and the reckoning of time. Allah has not created this but in truth. He details the Signs for a people who have knowledge. Indeed, in the alternation of night and day, and in all that Allah has created in the heavens and the earth there are Signs for a God-fearing people. (Al Quran 10:6-7)

Further more the Holy Quran anticipates the discovery of gravitation when it says in Sura Raad:

Allah is He Who raised up the heavens without any pillars that you can see. Then He settled Himself on the Throne. And He pressed the sun and the moon into service: each pursues its course until an appointed term. He regulates it all. He clearly explains the Signs, that you may have a firm belief in the meeting with your Lord. (Al Quran 13:3)

Mathematics is the metaphor against which all other sciences are checked. Sciences like astronomy and physics could not have developed without the foundation of mathematics and algebra provided by al-Khwārizmī and other Muslim mathematicians and astronomers.

How did the Holy Quran trigger the development of science and mathematics among the early Muslims? The best way to understand this is to note the close relation between astronomy and mathematics. The Holy Quran inspired the believers to study the phenomena of nature and showed them the connections between astronomy and mathematics, for example:

And We have made the night and the day two Signs, and the Sign of night We have made dark, and the Sign of day We have made sightgiving, that you may seek bounty from your Lord, and that you may know the computation of years and the science of reckoning and mathematics. And everything We have explained with a detailed explanation. (Al Quran 17:13)

And:

He it is Who made the sun radiate a brilliant light and the moon reflect a lustre, and ordained for it stages, that you might know the number of years and the reckoning of time. Allah has not created this but in truth. He details the Signs for a people who have knowledge. Indeed, in the alternation of night and day, and in all that Allah has created in the heavens and the earth there are Signs for a God-fearing people. (Al Quran 10:6-7)

Prof. David M Bressoud explains the close relationship between astronomy and mathematics in his lecture series, The Queen of Sciences: a History of Mathematics:

A third source of the patterns of mathematics is astronomy or astrology.

The ancients made no clear distinction between these two fields. They studied the heavens to try to understand what was likely to happen on earth.

Some of the greatest astronomers, including Johannes Kepler were also astrologers. Kepler’s work in both astronomy and astrology would lay the foundations for much of the development of calculus.This lack of distinction between astronomers and astrologers carried over to mathematicians. The emperor Tiberius is said to have banished all “mathematicians” from Rome. In fact he banished the astrologers, who were predicting his downfall.

Some of this confusion stems from the fact that important advances in mathematics came directly out of astronomy. By looking at the heavens, mathematicians were able to pick out patterns in much purer form than they could in the world around them.[1]

Astronomy was one of the dominant forces behind the development of mathematics. Most people think of trigonometry in connection with land measurement and today it is used in surveying, but it was originally applied to the study of astronomical phenomena.[2]

As we noted before, there are almost 750 verses in the Holy Quran inspiring believers to study the phenomena of nature, many are pertaining to the study of astronomy and a few emphasize quantitive study, for example, “The sun and the moon run their courses according to a fixed reckoning and calculation.” (Al Quran 55:6) The word used in this verse is بِحُسْبَانٍۙ the Arabic word for mathematics is derived from the same root as this word. Quoting from a wikipedia article, Mathematics in medieval Islam:

A major impetus for the flowering of mathematics as well as astronomy in medieval Islam came from religious observances, which presented an assortment of problems in astronomy and mathematics, specifically in trigonometry, spherical geometry, algebra and arithmetic.

The Islamic law of inheritance served as an impetus behind the development of algebra (derived from the Arabic al-jabr) by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī and other medieval Islamic mathematicians. Al-Khwārizmī’s Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala devoted a chapter on the solution to the Islamic law of inheritance using algebra. He formulated the rules of inheritance as linear equations, hence his knowledge of quadratic equations was not required. Later mathematicians who specialized in the Islamic law of inheritance included Al-Hassār, who developed the modern symbolic mathematical notation for fractions in the 12th century.[3]

The Father of Algebra: Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī https://t.co/SbhCl3a7is via @wordpressdotcom

— Rafiq A. TSCHANNEN (@MuslimPoly) November 11, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Mathematics for renaissance

Mark Graham is the Edgar award-winning author of ‘Black Maria,’ third in a series of historical novels which have been translated into several languages. He studied medieval history and religious studies at Connecticut College and has a master’s degree in English literature from Kutztown University. He writes:

Throughout the Middle Ages, Europe used Roman numerals. Like the Greeks before them, Romans based their numerical system on letters. It was a relatively small stock of symbols, seven in total: I, V, X, L, C, D, M, representing 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000. Despite its simplicity, some problems remained. Writing out larger numbers could be cumbersome. For example, 1938 is MCMXXXVIII. In multiplication it was even worse: 57 X 38 = 2166 becomes LVII by XXXVIII = MMCLXVI. This unwieldy system made calculation of large numbers a tedious and time-consuming affair. Arithmetic was largely left to a few specialists who had plenty of time on their hands.

That was until Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi joined the House of Wisdom in the early ninth century. A great astronomer who also created an early table cataloguing the latitude and longitude of over 2,000 cities, al-Khwarizmi is primarily known today as one of the most influential mathematicians of all time. His seminal book Calculation of Integration and Equation changed mathematics forever.

If you’re wondering how, a clue is in the Arabic title: Hisab al-Jabr w-al-Muqabalah. Look closely and you’ll notice an English word hiding in there.

AI-jabr-or in English, algebra.

Al-Khwarizmi may not have invented algebra in the modern sense.

The credit goes to the Hindus for first practicing this mathematical art. But it was al- Khwarizmi who introduced algebra to the West. His style was so clear and authoritative that his volume became the standard mathematical text in Europe for four hundred years.When the book was translated into Latin three hundred years later as Liber Algorismi, it made al-Khwarizmi’s Latinized name a household word synonymous with arithmetic itself Our English word “algorithm” is a tribute to this greatest of Muslim mathematicians.

Al-Khwarizmi was dazzled by Hindu mathematics. Seeing the vast potential of its numeric and decimal systems, he wrote several works that introduced Hindu math to Islam. The numbers were so easy to use that they soon became the standard throughout the Muslim world. With the publication of his Liber Algorismi in Europe these Hindu numerals became known as Arabic numerals, a gift of the Islamic world to Christendom.

The most astounding number the Arabs showed them was not a number at all, but the lack of one: zero. Muslim mathematicians represented this lack of number by a dot or small circle. They called it sifr, an empty object. This word was the source of the English ‘zero’ as well as “cipher.” Sift solved a lot of problems in mathematics. It allowed for the expression of difference between two equal quantities as well as positional notation, where the digit’s position has a value itself which, combining with the value of the digit, creates the number’s value. It was a bold new step in abstraction that led to the higher mathematics of the Renaissance.[4]

This concludes my article, for my references please see the very end of this post.

@The_MuslimTimes Heritage – The Father of Algebra: Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī – https://t.co/BhnLgVtUFR pic.twitter.com/JcYOPtScfq

— Salma Javid Khan (@SalmaJavidKhan) November 15, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

His Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala presented the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. He is considered the founder of algebra,[7] a credit he shares with Diophantus. In the twelfth century, Latin translations of his work on the Indian numerals, introduced the decimal positional number system to the Western world.[4] He revised Ptolemy‘s Geography and wrote on astronomy and astrology.

His contributions had a great impact on language. “Algebra” is derived from al-jabr, one of the two operations he used to solve quadratic equations. Algorism and algorithm stem from Algoritmi, the Latin form of his name.[8] His name is the origin of (Spanish) guarismo[9] and of (Portuguese) algarismo, both meaning digit.

Life

Few details of al-Khwārizmī’s life are known with certainty, even his birthplace is unsure. His name may indicate that he came from Khwarezm (Khiva), then in Greater Khorasan, which occupied the eastern part of the Greater Iran, now Xorazm Province in Uzbekistan. Abu Rayhan Biruni calls the people of Khwarizm “a branch of the Persian tree”.[10]

Al-Tabari gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسـيّ القطربّـليّ). The epithet al-Qutrubbulli could indicate he might instead have come from Qutrubbul (Qatrabbul)[11], a viticulture district near Baghdad. However, Rashed[12] points out that:

There is no need to be an expert on the period or a philologist to see that al-Tabari’s second citation should read “Muhammad ibn Mūsa al-Khwārizmī and al-Majūsi al-Qutrubbulli,” and that there are two people (al-Khwārizmī and al-Majūsi al-Qutrubbulli) between whom the letter wa [Arabic ‘و’ for the article ‘and’] has been omitted in an early copy. This would not be worth mentioning if a series of errors concerning the personality of al-Khwārizmī, occasionally even the origins of his knowledge, had not been made. Recently, G. J. Toomer … with naive confidence constructed an entire fantasy on the error which cannot be denied the merit of amusing the reader.

Regarding al-Khwārizmī’s religion, Toomer writes:

Another epithet given to him by al-Ṭabarī, “al-Majūsī,” would seem to indicate that he was an adherent of the old Zoroastrian religion. This would still have been possible at that time for a man of Iranian origin, but the pious preface to al-Khwārizmī’s Algebra shows that he was an orthodox Muslim, so al-Ṭabarī’s epithet could mean no more than that his forebears, and perhaps he in his youth, had been Zoroastrians.[5]

In Ibn al-Nadīm‘s Kitāb al-Fihrist we find a short biography on al-Khwārizmī, together with a list of the books he wrote. Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists from as far as China and India traveled to this city, as did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the House of Wisdom established by Caliph al-Maʾmūn, where he studied the sciences and mathematics, which included the translation of Greek and Sanskrit scientific manuscripts.

Contributions

Al-Khwārizmī’s contributions to mathematics, geography, astronomy, and cartography established the basis for innovation in algebra and trigonometry. His systematic approach to solving linear and quadratic equations led to algebra, a word derived from the title of his 830 book on the subject, “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing” (al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa’l-muqabalaالكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة).

On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals written about 825, was principally responsible for spreading the Indian system of numeration throughout the Middle East and Europe. It was translated into Latin as Algoritmi de numero Indorum. Al-Khwārizmī, rendered as (Latin) Algoritmi, led to the term “algorithm“.

Some of his work was based on Persian and Babylonian astronomy, Indian numbers, and Greek mathematics.

Al-Khwārizmī systematized and corrected Ptolemy‘s data for Africa and the Middle east. Another major book was Kitab surat al-ard (“The Image of the Earth”; translated as Geography), presenting the coordinates of places based on those in the Geography of Ptolemy but with improved values for the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, and Africa.

He also wrote on mechanical devices like the astrolabe and sundial.

He assisted a project to determine the circumference of the Earth and in making a world map for al-Ma’mun, the caliph, overseeing 70 geographers.[13]

When, in the 12th century, his works spread to Europe through Latin translations, it had a profound impact on the advance of mathematics in Europe. He introduced Arabic numerals into the Latin West, based on a place-value decimal system developed from Indian sources.[14]

Algebra

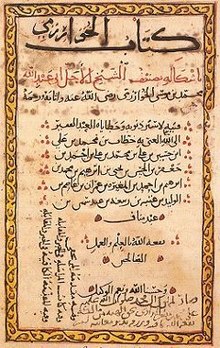

Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة, ‘The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing’) is a mathematical book written approximately 830 CE. The book was written with the encouragement of the Caliph al-Ma’mun as a popular work on calculation and is replete with examples and applications to a wide range of problems in trade, surveying and legal inheritance[15]. The term algebra is derived from the name of one of the basic operations with equations (al-jabr, meaning completion, or, subtracting a number from both sides of the equation) described in this book. The book was translated in Latin as Liber algebrae et almucabala by Robert of Chester (Segovia, 1145) hence “algebra”, and also by Gerard of Cremona. A unique Arabic copy is kept at Oxford and was translated in 1831 by F. Rosen. A Latin translation is kept in Cambridge.[16]

This book is considered the foundational text of modern algebra. It provided an exhaustive account of solving polynomial equations up to the second degree,[17] and introduced the fundamental methods of “reduction” and “balancing”, referring to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation.[18]

Al-Khwārizmī’s method of solving linear and quadratic equations worked by first reducing the equation to one of six standard forms (where b and c are positive integers)

- squares equal roots (ax2 = bx)

- squares equal number (ax2 = c)

- roots equal number (bx = c)

- squares and roots equal number (ax2 + bx = c)

- squares and number equal roots (ax2 + c = bx)

- roots and number equal squares (bx + c = ax2)

by dividing out the coefficient of the square and using the two operations al-jabr (Arabic: الجبر “restoring” or “completion”) and al-muqābala (“balancing”). Al-jabr is the process of removing negative units, roots and squares from the equation by adding the same quantity to each side. For example, x2 = 40x − 4x2 is reduced to 5x2 = 40x. Al-muqābala is the process of bringing quantities of the same type to the same side of the equation. For example, x2 + 14 = x + 5 is reduced to x2 + 9 = x.

The above discussion uses modern mathematical notation for the types of problems which the book discusses. However, in al-Khwārizmī’s day, most of this notation had not yet been invented, so he had to use ordinary text to present problems and their solutions. For example, for one problem he writes, (from an 1831 translation)

“If some one say: “You divide ten into two parts: multiply the one by itself; it will be equal to the other taken eighty-one times.” Computation: You say, ten less thing, multiplied by itself, is a hundred plus a square less twenty things, and this is equal to eighty-one things. Separate the twenty things from a hundred and a square, and add them to eighty-one. It will then be a hundred plus a square, which is equal to a hundred and one roots. Halve the roots; the moiety is fifty and a half. Multiply this by itself, it is two thousand five hundred and fifty and a quarter. Subtract from this one hundred; the remainder is two thousand four hundred and fifty and a quarter. Extract the root from this; it is forty-nine and a half. Subtract this from the moiety of the roots, which is fifty and a half. There remains one, and this is one of the two parts.”[15]

In modern notation this process, with ‘x’ the “thing” (shay’) or “root”, is given by the steps,

- (10 − x)2 = 81x

- x2 + 100 = 101x

Let the roots of the equation be ‘p’ and ‘q’. Then  , pq = 100 and

, pq = 100 and

So a root is given by

Several authors have also published texts under the name of Kitāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala, including |Abū Ḥanīfa al-Dīnawarī, Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam, Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdlī, Abū Yūsuf al-Miṣṣīṣī, ‘Abd al-Hamīd ibn Turk, Sind ibn ʿAlī, Sahl ibn Bišr, and Šarafaddīn al-Ṭūsī.

J. J. O’Conner and E. F. Robertson wrote in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

“Perhaps one of the most significant advances made by Arabic mathematics began at this time with the work of al-Khwarizmi, namely the beginnings of algebra. It is important to understand just how significant this new idea was. It was a revolutionary move away from the Greek concept of mathematics which was essentially geometry. Algebra was a unifying theory which allowed rational numbers, irrational numbers, geometrical magnitudes, etc., to all be treated as “algebraic objects”. It gave mathematics a whole new development path so much broader in concept to that which had existed before, and provided a vehicle for future development of the subject. Another important aspect of the introduction of algebraic ideas was that it allowed mathematics to be applied to itself in a way which had not happened before.”[19]

R. Rashed and Angela Armstrong write:

“Al-Khwarizmi’s text can be seen to be distinct not only from the Babylonian tablets, but also from Diophantus‘ Arithmetica. It no longer concerns a series of problems to be resolved, but an exposition which starts with primitive terms in which the combinations must give all possible prototypes for equations, which henceforward explicitly constitute the true object of study. On the other hand, the idea of an equation for its own sake appears from the beginning and, one could say, in a generic manner, insofar as it does not simply emerge in the course of solving a problem, but is specifically called on to define an infinite class of problems.”[20]

Arithmetic

Al-Khwārizmī’s second major work was on the subject of arithmetic, which survived in a Latin translation but was lost in the original Arabic. The translation was most likely done in the twelfth century by Adelard of Bath, who had also translated the astronomical tables in 1126.

The Latin manuscripts are untitled, but are commonly referred to by the first two words with which they start: Dixit algorizmi (“So said al-Khwārizmī”), or Algoritmi de numero Indorum (“al-Khwārizmī on the Hindu Art of Reckoning”), a name given to the work by Baldassarre Boncompagni in 1857. The original Arabic title was possibly Kitāb al-Jamʿ wa-l-tafrīq bi-ḥisāb al-Hind[21] (“The Book of Addition and Subtraction According to the Hindu Calculation”)[22]

Al-Khwarizmi’s work on arithmetic was responsible for introducing the Arabic numerals, based on the Hindu-Arabic numeral system developed in Indian mathematics, to the Western world. The term “algorithm” is derived from the algorism, the technique of performing arithmetic with Hindu-Arabic numerals developed by al-Khwarizmi. Both “algorithm” and “algorism” are derived from the Latinized forms of al-Khwarizmi’s name, Algoritmi and Algorismi, respectively.

Trigonometry

In trigonometry, al-Khwārizmī (c. 780-850) produced tables for the trigonometric functions of sines and cosine in the Zīj al-Sindhind,[23] alongside the first tables for tangents. He was also an early pioneer in spherical trigonometry, and wrote a treatise on the subject.[19]

Astronomy

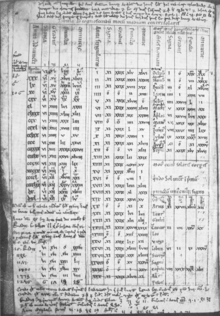

Al-Khwārizmī’s Zīj al-Sindhind[5] (Arabic: زيج “astronomical tables of Sind and Hind“) is a work consisting of approximately 37 chapters on calendrical and astronomical calculations and 116 tables with calendrical, astronomical and astrological data, as well as a table of sine values. This is the first of many Arabic Zijes based on the Indian astronomical methods known as the sindhind.[23] The work contains tables for the movements of the sun, the moon and the five planets known at the time. This work marked the turning point in Islamic astronomy. Hitherto, Muslim astronomers had adopted a primarily research approach to the field, translating works of others and learning already discovered knowledge. Al-Khwarizmi’s work marked the beginning of non-traditional methods of study and calculations.[24]

The original Arabic version (written c. 820) is lost, but a version by the Spanish astronomer Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti (c. 1000) has survived in a Latin translation, presumably by Adelard of Bath (January 26, 1126).[25] The four surviving manuscripts of the Latin translation are kept at the Bibliothèque publique (Chartres), the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris), the Bibliotheca Nacional (Madrid) and the Bodleian Library (Oxford).

Al-Khwarizmi made several important improvements to the theory and construction of sundials, which he inherited from his Indian and Hellenistic predecessors. He made tables for these instruments which considerably shortened the time needed to make specific calculations. His sundial was universal and could be observed from anywhere on the Earth. From then on, sundials were frequently placed on mosques to determine the time of prayer.[26] The shadow square, an instrument used to determine the linear height of an object, in conjunction with the alidade for angular observations, was also invented by al-Khwārizmī in ninth-century Baghdad.[27][not in citation given]

The first quadrants and mural instruments were invented by al-Khwarizmi in ninth century Baghdad.[28][not in citation given] The sine quadrant, invented by al-Khwārizmī, was used for astronomical calculations.[29][not in citation given] The first horary quadrant for specific latitudes, was also invented by al-Khwārizmī in Baghdad, then center of the development of quadrants.[29][not in citation given] It was used to determine time (especially the times of prayer) by observations of the Sun or stars.[30] The Quadrans Vetus was a universal horary quadrant, an ingenious mathematical device invented by al-Khwarizmi in the ninth century and later known as the Quadrans Vetus (Old Quadrant) in medieval Europe from the thirteenth century. It could be used for any latitude on Earth and at any time of the year to determine the time in hours from the altitude of the Sun. This was the second most widely used astronomical instrument during the Middle Ages after the astrolabe. One of its main purposes in the Islamic world was to determine the times of Salah.[29][not in citation given]

Geography

Hubert Daunicht’s reconstruction of al-Khwārizmī’s planisphere.

Al-Khwārizmī’s third major work is his Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض “Book on the appearance of the Earth” or “The image of the Earth” translated as Geography), which was finished in 833. It is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy‘s Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.[31]

There is only one surviving copy of Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ, which is kept at the Strasbourg University Library. A Latin translation is kept at the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. The complete title translates as Book of the appearance of the Earth, with its cities, mountains, seas, all the islands and rivers, written by Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī, according to the geographical treatise written by Ptolemy the Claudian.

The book opens with the list of latitudes and longitudes, in order of “weather zones”, that is to say in blocks of latitudes and, in each weather zone, by order of longitude. As Paul Gallez points out, this excellent system allows us to deduce many latitudes and longitudes where the only document in our possession is in such a bad condition as to make it practically illegible.

Neither the Arabic copy nor the Latin translation include the map of the world itself, however Hubert Daunicht was able to reconstruct the missing map from the list of coordinates. Daunicht read the latitudes and longitudes of the coastal points in the manuscript, or deduces them from the context where they were not legible. He transferred the points onto graph paper and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map. He then does the same for the rivers and towns.[32]

Al-Khwārizmī corrected Ptolemy’s gross overestimate for the length of the Mediterranean Sea[33] (from the Canary Islands to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean); Ptolemy overestimated it at 63 degrees of longitude, while al-Khwarizmi almost correctly estimated it at nearly 50 degrees of longitude. He “also depicted the Atlantic and Indian Oceans as open bodies of water, not land-locked seas as Ptolemy had done.”[34] Al-Khwarizmi thus set the Prime Meridian of the Old World at the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, 10–13 degrees to the east of Alexandria (the prime meridian previously set by Ptolemy) and 70 degrees to the west of Baghdad. Most medieval Muslim geographers continued to use al-Khwarizmi’s prime meridian.[33]

Jewish calendar

Al-Khwārizmī wrote several other works including a treatise on the Hebrew calendar (Risāla fi istikhrāj taʾrīkh al-yahūd “Extraction of the Jewish Era”). It describes the 19-year intercalation cycle, the rules for determining on what day of the week the first day of the month Tishrī shall fall; calculates the interval between the Jewish era (creation of Adam) and the Seleucid era; and gives rules for determining the mean longitude of the sun and the moon using the Jewish calendar. Similar material is found in the works of al-Bīrūnī and Maimonides.[5]

Other works

Several Arabic manuscripts in Berlin, Istanbul, Tashkent, Cairo and Paris contain further material that surely or with some probability comes from al-Khwārizmī. The Istanbul manuscript contains a paper on sundials, which is mentioned in the Fihirst. Other papers, such as one on the determination of the direction of Mecca, are on the spherical astronomy.

Two texts deserve special interest on the morning width (Maʿrifat saʿat al-mashriq fī kull balad) and the determination of the azimuth from a height (Maʿrifat al-samt min qibal al-irtifāʿ).

He also wrote two books on using and constructing astrolabes. Ibn al-Nadim in his Kitab al-Fihrist (an index of Arabic books) also mentions Kitāb ar-Ruḵāma(t) (the book on sundials) and Kitab al-Tarikh (the book of history) but the two have been lost.

The shaping of our mathematics can be attributed to Al-Khwarizmi, the chief librarian of the observatory, research center and library called the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. His treatise, “Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala” (Calculation by Restoration and Reduction), which covers linear and quadratic equations, solved trade imbalances, inheritance questions and problems arising from land surveyance and allocation. In passing, he also introduced into common usage our present numerical system, which replaced the old, cumbersome Roman one.

See also

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: al-Khwārizmī |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi |

- Al-Khwarizmi (crater) — A crater on the far side of the moon named after al-Khwārizmī.

- Khwarizmi International Award — An Iranian award named after al-Khwārizmī.

- Mathematics in medieval Islam

- Astronomy in medieval Islam

Notes

- ^ There is some confusion in the literature on whether al-Khwārizmī’s full name is Abū ʿAbdallāh Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī or Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. Ibn Khaldun notes in his encyclopedic work: “The first who wrote upon this branch (algebra) was Abu ʿAbdallah al-Khowarizmi, after whom came Abu Kamil Shojaʿ ibn Aslam.” (MacGuckin de Slane). (Rosen 1831, pp. xi–xiii) mentions that “[Abu Abdallah Mohammed ben Musa] lived and wrote under the caliphat of Al Mamun, and must therefore be distinguished from Abu Jafar Mohammed ben Musa, likewise a mathematician and astronomer, who flourished under the Caliph Al Motaded (who reigned A.H. 279-289, A.D. 892-902).” Karpinski notes in his review on (Ruska 1917) that in (Ruska 1918): “Ruska here inadvertently speaks of the author as Abū Gaʿfar M. b. M., instead of Abū Abdallah M. b. M.”

- ^ a b Hogendijk, Jan P. (1998). “al-Khwarzimi” ([dead link]). Pythagoras 38 (2): 4–5. ISSN 0033–4766. http://www.kennislink.nl/web/show?id=116543.

- ^ Berggren 1986

- ^ a b Struik 1987, p. 93

- ^ a b c d Toomer 1990

- ^ Oaks, Jeffrey A.. “Was al-Khwarizmi an applied algebraist?”. University of Indianapolis. http://facstaff.uindy.edu/~oaks/MHMC.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ Gandz 1936

- ^ Daffa 1977

- ^ Knuth, Donald (1979). Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computer Science. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-11157-3. http://historical.ncstrl.org/litesite-data/stan/CS-TR-80-786.pdf.

- ^ Abu Rahyan Biruni, “Athar al-Baqqiya ‘an al-Qurun al-Xaliyyah”(Vestiges of the past: the chronology of ancient nations), Tehran, Miras-e-Maktub, 2001. Original Arabic of the quote: “و أما أهل خوارزم، و إن کانوا غصنا ً من دوحة الفُرس” (pg. 56)

- ^ “Iraq After the Muslim Conquest”, by Michael G. Morony, ISBN 1593333153 (a 2005 facsimile from the original 1984 book), p. 145

- ^ Rashed, Roshdi (1988). “al-Khwārizmī’s Concept of Algebra”. in Zurayq, Qusṭanṭīn; Atiyeh, George Nicholas; Oweiss, Ibrahim M.. Arab Civilization: Challenges and Responses : Studies in Honor of Constantine K. Zurayk. SUNY Press. p. 108. ISBN 0887066984. http://books.google.com/books?id=JXbXRKRY_uAC&pg=PA108&dq=Qutrubbulli#PPA108,M1

- ^ “al-Khwarizmi”. Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9045366. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ “Khwarizmi, Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Musa al-” in Oxford Islamic Studies Online

- ^ a b Rosen, Frederic. The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, al-Khwārizmī”. 1831 English Translation. http://www.wilbourhall.org/index.html#algebra The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ Karpinski, L. C. (1912). “History of Mathematics in the Recent Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica”. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1991). “The Arabic Hegemony”. A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 228. ISBN 0471543977.

“The Arabs in general loved a good clear argument from premise to conclusion, as well as systematic organization — respects in which neither Diophantus nor the Hindus excelled.” - ^ (Boyer 1991, “The Arabic Hegemony” p. 229) “It is not certain just what the terms al-jabr and muqabalah mean, but the usual interpretation is similar to that implied in the translation above. The word al-jabr presumably meant something like “restoration” or “completion” and seems to refer to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation; the word muqabalah is said to refer to “reduction” or “balancing” — that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation.”

- ^ a b O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Khwarizmi.html .

- ^ Rashed, R.; Armstrong, Angela (1994). The Development of Arabic Mathematics. Springer. pp. 11–2. ISBN 0792325656. OCLC 29181926

- ^ Ruska

- ^ Berggren 1986, p. 7

- ^ a b Kennedy 1956, pp. 26–9

- ^ (Dallal 1999, p. 163)

- ^ Kennedy 1956, p. 128

- ^ (King 1999a, pp. 168–9)

- ^ David A. King (2002), “A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus”, Journal for the History of Astronomy 33: 237-255 [238-9]

- ^ David A. King, “Islamic Astronomy”, in Christopher Walker (1999), ed., Astronomy before the telescope, p. 167-168. British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2733-7.

- ^ a b c (King 2002, pp. 237–238)

- ^ (King 1999a, pp. 167–8)

- ^ “The history of cartography”. GAP computer algebra system. http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Cartography.html. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ Daunicht

- ^ a b Edward S. Kennedy, Mathematical Geography, p. 188, in (Rashed & Morelon 1996, pp. 185–201)

- ^ Covington, Richard (2007). Saudi Aramco World, May–June 2007: 17–21. http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200703/the.third.dimension.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-06

Further reading

- Biographical

- Toomer, Gerald (1990). “Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā”. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 7. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 0-684-16962-2.

- Dunlop, Douglas Morton (1943). “Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland (Cambridge University): 248–250.

- O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Khwarizmi.html .

- Fuat Sezgin. Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums. 1974, E. J. Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands.

- Sezgin, F., ed., Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy, Frankfurt: Institut für Geschichte der arabisch-islamischen Wissenschaften, 1997–9.

- Algebra

- Gandz, Solomon (November 1926). “The Origin of the Term “Algebra””. The American Mathematical Monthly (The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 33, No. 9) 33 (9): 437–440. doi:10.2307/2299605. ISSN 0002–9890. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9890%28192611%2933%3A9%3C437%3ATOOTT%22%3E2.0.CO%3B2–0.

- Gandz, Solomon (1936). “The Sources of al-Khowārizmī’s Algebra”. Osiris 1 (1): 263–277. doi:10.1086/368426. ISSN 0369–7827. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0369-7827%28193601%291%3A1%3C263%3ATSOAA%3E2.0.CO%3B2–3.

- Gandz, Solomon (1938). “The Algebra of Inheritance: A Rehabilitation of Al-Khuwārizmī”. Osiris 5 (5): 319–391. doi:10.1086/368492. ISSN 0369–7827. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0369-7827%281938%291%3A5%3C319%3ATAOIAR%3E2.0.CO%3B2–2.

- Hughes, Barnabas (1986). “Gerard of Cremona’s Translation of al-Khwārizmī’s al-Jabr: A Critical Edition”. Mediaeval Studies 48: 211–263.

- Barnabas Hughes. Robert of Chester’s Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi’s al-Jabr: A new critical edition. In Latin. F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden (1989). ISBN 3-515-04589-9.

- Karpinski, L. C. (1915). Robert of Chester’s Latin Translation of the Algebra of Al-Khowarizmi: With an Introduction, Critical Notes and an English Version. The Macmillan Company. http://library.albany.edu/preservation/brittle_bks/khuwarizmi_robertofchester/.

- Rosen, Fredrick (1831). The Algebra of Mohammed Ben Musa. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4179-4914-7. http://www.archive.org/details/algebraofmohamme00khuwrich.

- Ruska, Julius. “Zur ältesten arabischen Algebra und Rechenkunst”. Isis.

- Arithmetic

- Folkerts, Menso (1997) (in German and Latin). Die älteste lateinische Schrift über das indische Rechnen nach al-Ḫwārizmī. München: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7696-0108-4.

- Astronomy

- Goldstein, B. R. (1968). Commentary on the Astronomical Tables of Al-Khwarizmi: By Ibn Al-Muthanna. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300004982.

- Hogendijk, Jan P. (1991). “Al-Khwārizmī’s Table of the “Sine of the Hours” and the Underlying Sine Table”. Historia Scientiarum 42: 1–12.

- King, David A. (1983). Al-Khwārizmī and New Trends in Mathematical Astronomy in the Ninth Century. New York University: Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies: Occasional Papers on the Near East 2. LCCN 85-150177.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1962). The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi.

- Rosenfeld, Boris A. (1993). Menso Folkerts and J. P. Hogendijk. ed. “”Geometric trigonometry” in treatises of al-Khwārizmī, al-Māhānī and Ibn al-Haytham”. Vestiga mathematica: Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Mathematics in Honour of H. L. L. Busard (Amsterdam: Rodopi). ISBN 90-5183-536-1.

- Suter, H. [Ed.]: Die astronomischen Tafeln des Muhammed ibn Mûsâ al-Khwârizmî in der Bearbeitung des Maslama ibn Ahmed al-Madjrîtî und der latein. Übersetzung des Athelhard von Bath auf Grund der Vorarbeiten von A. Bjørnbo und R. Besthorn in Kopenhagen. Hrsg. und komm. Kopenhagen 1914. 288 pp. Repr. 1997 (Islamic Mathematics and Astronomy. 7). ISBN 3-8298-4008-X.

- Van Dalen, B. Al-Khwarizmi’s Astronomical Tables Revisited: Analysis of the Equation of Time.

- Jewish calendar

- Kennedy, E. S. (1964). “Al-Khwārizmī on the Jewish Calendar”. Scripta Mathematica 27: 55–59.

- Geography

- Daunicht, Hubert (1968–1970) (in German). Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs : Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens. Bonner orientalistische Studien. N.S.; Bd. 19. LCCN 71-468286.

- Mžik, Hanz von (1915). “Ptolemaeus und die Karten der arabischen Geographen”. Mitteil. D. K. K. Geogr. Ges. In Wien 58: 152.

- Mžik, Hanz von (1916). “Afrika nach der arabischen Bearbeitung der γεωγραφικὴ ὑφήγησις des Cl. Ptolomeaus von Muh. ibn Mūsa al-Hwarizmi”. Denkschriften d. Akad. D. Wissen. In Wien, Phil.-hist. Kl. 59.

- Mžik, Hanz von (1926). Das Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ des Abū Ǧa‘far Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḫuwārizmī. Leipzig.

- Nallino, C. A. (1896), “Al-Ḫuwārizmī e il suo rifacimento della Geografia di Tolemo”, Atti della R. Accad. dei Lincei, Arno 291, Serie V, Memorie, Classe di Sc. Mor., Vol. II, Rome

- Ruska, Julius (1918). “Neue Bausteine zur Geschichte der arabischen Geographie”. Geographische Zeitschrift 24: 77–81.

- Spitta, W. (1879). “Ḫuwārizmī’s Auszug aus der Geographie des Ptolomaeus”. Zeitschrift Deutschen Morgenl. Gesell. 33.

General references

- For a more extensive bibliography see: History of mathematics, Mathematics in medieval Islam, and Astronomy in medieval Islam.

- Berggren, J. Lennart (1986). Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 0-387-96318-9

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). “The Arabic Hegemony”. A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0471543977.

- Daffa, Ali Abdullah al- (1977). The Muslim contribution to mathematics. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-85664-464-1

- Dallal, Ahmad (1999). “Science, Medicine and Technology”. in Esposito, John. The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press, New York

- Kennedy, E.S. (1956). A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables; Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 46. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society

- King, David A. (1999a). “Islamic Astronomy”. in Walker, Christopher. Astronomy before the telescope. British Museum Press. pp. 143–174. ISBN 0-7141-2733-7

- King, David A. (2002). “A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus”. Journal for the History of Astronomy 33: 237–255

- Struik, Dirk Jan (1987). A Concise History of Mathematics (4th ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0486602559

- O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Abraham.html .

- O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Arabic_mathematics.html .

- Roshdi Rashed, The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra, London, 1994.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

My References other than Wikipedia

-

- Prof. David M Bressoud. The Queen of Sciences: a History of Mathematics. The Teaching Company Guidebook on this lecture series, 2008. Page 5.

- Prof. David M Bressoud. The Queen of Sciences: a History of Mathematics. The Teaching Company Guidebook on this lecture series, 2008. Page 29.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathematics_in_medieval_Islam

- Mark Graham. How Islam Created the Modern World. Amana Publications, 2006. Pages 63-65.

</ol

Categories: Mathematics, Muslim Heritage, Qur'an, Quran, Religion & Science, The Muslim Times

Very interesting articles!