As all humans are God’s creation, it stands to reason that God not only guided people in the Middle East through Abraham, Isaac, David, Solomon, Jeremiah, John the Baptist and Jesus, but, He also guided other people through prophets like Confucius, Buddha and Zoroaster. If this be true there should be some common theme between their teachings, a common thread, a clue that these teachings are all emanating from a common source, one and the same glacier feeds all these rivers of wisdom.

Absence of Trinity, Original Sin and Pauline atonement in Buddha’s teachings should serve as an epiphany to every fair and open minded Christian.

This is not just a Muslim paradigm but some Christian missionaries have yielded to this frame of reasoning. Don Richardson is a Canadian Christian missionary, who worked among the tribal people of Western New Guinea, Indonesia. He argues in his writings that, hidden among tribal cultures, there are usually some practices or understandings, which he calls ‘Redemptive Analogies,’ which can be used to illustrate the meaning of the Christian Gospel.

In 1962, he and his wife Carol went to work among the Sawi tribe of what was then Dutch New Guinea. Richardson labored to show the villagers a way that they could comprehend Jesus from the Bible, but the cultural barriers to understanding and accepting this teaching seemed impossible until an unlikely event brought the concept of the substitutionary atonement of Christ into immediate relevance for the Sawi.

Missionary historian Ruth A. Tucker writes:

“As he learned the language and lived with the people, he became more aware of the gulf that separated his Christian worldview from the worldview of the Sawi: ‘In their eyes, Judas, not Jesus, was the hero of the Gospels, Jesus was just the dupe to be laughed at.’ Eventually Richardson discovered what he referred to as a Redemptive Analogy that pointed to the Incarnate Christ far more clearly than any biblical passage alone could have done. What he discovered was the Sawi concept of the Peace Child.”

Three tribal villages were in constant battle at this time. The Richardsons were considering leaving the area, so to keep them there, the Sawi people in the embattled villages came together and decided that they would make peace with their hated enemies. Ceremonies commenced that saw young children being exchanged between opposing villages. Observing this, Richardson wrote: “if a man would actually give his own son to his enemies, that man could be trusted!” From this rare picture came the analogy of God’s sacrifice of his own Son. The Sawi began to understand the teaching of the incarnation of Christ in the Gospel after Richardson explained God to them in this way.

This time Don Richardson had duped them into a different irrationality. If we apply the principles of ‘Redemptive Analogy’ to reformers and prophets like Confucius, Buddha and Zoroaster we will realize quickly that Unitarianism is the way to go!

Contents

The testimony of One God is everywhere and Trinity is no where to be seen in our universe. The universe and all life forms on our planet earth speak of One God and not three.Historically also other than the Christians we find no testimony of Trinity in other regions of the earth and other religions. Even looking at the local population of the Middle East, Jews are strict monotheists. Even among the Christians we still have a sect named Unitarians.

The word Trinity is not even mentioned in the New Testament. It is stated in 1890 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica, “The Trinitarians and the Unitarians continued to confront each other, the latter at the beginning of the third century still forming the large majority.”

Prophet Buddha

From the time I was capable of conceiving an idea, and acting upon it by reflection, I either doubted the truth of the Christian system, or thought it to be a strange affair; I scarcely knew which it was: but I well remember, when about seven or eight years of age, hearing a sermon read by a relation of mine, who was a great devotee of the church, upon the subject of what is called Redemption by the death of the Son of God. After the sermon was ended, I went into the garden, and as I was going down the garden steps (for I perfectly recollect the spot) I revolted at the recollection of what I had heard, and thought to myself that it was making God Almighty act like a passionate man, that killed his son, when he could not revenge himself any other way; and as I was sure a man would be hanged that did such a thing, I could not see for what purpose they preached such sermons. This was not one of those kind of thoughts that had anything in it of childish levity; it was to me a serious reflection, arising from the idea I had that God was too good to do such an action, and also too almighty to be under any necessity of doing it. I believe in the same manner to this moment; and I moreover believe, that any system of religion that has anything in it that shocks the mind of a child, cannot be a true system. (Thomas Paine)

In an article published in Muslim Sunrise in 2006, The Concept of God in Buddhism, Imran Ghumman traces the concept of One God in early Buddhism. He writes:”‘Confess and believe in God (Is’ana) who is the worthy object of obedience…… Oh strive ye to obtain this inestimable treasure’ …said Buddha as quoted by King Ashoka in one of his inscriptions at Pardohli, a rock located in the Eastern bank of the river Katak, twenty miles from Jagan Nath, India.”

He outlines at least 7 proofs for his thesis that Buddha believed in One God, the One God of Moses, David, Solomon, Jesus and Muhammad, may peace be upon all of them. Read Imran Ghumman’s article online:

http://www.muslimsunrise.com/dmddocuments/2006_iss_1.pdf#page=19

Gautama, also known as Śākyamuni (“Sage of the Śākyas“), is the primary figure in Buddhism, and accounts of his life, discourses, and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition, and first committed to writing about 400 years later.

He is also regarded as a god or prophet in other religions such as Hinduism, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the Bahá’í faith.

Life

Traditional biographies

The primary sources for the life of Siddhārtha Gautama are in a variety of different and sometimes conflicting traditional biographies. These include the Buddhacarita, Lalitavistara Sūtra, Mahāvastu, and the Nidānakathā.[5] Of these, the Buddhacarita is the earliest full biography, an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa, and dating around the beginning of the 2nd century CE.[5] The Lalitavistara Sūtra is the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[6] The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda sect is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[6] Lastly, the Nidānakathā is from the Theravāda sect in Sri Lanka, composed in the 5th century CE by Buddhaghoṣa.[7]

From canonical sources, the Jātaka tales, Mahāpadāna Sutta (DN 14), and the Acchariyaabbhuta Sutta (MN 123) include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātaka tales retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[8] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Acchariyaabbhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama’s birth, such as the bodhisattva’s descent from Tuṣita Heaven into his mother’s womb.

Traditional biographies of Gautama generally include numerous miracles, omens, and supernatural events. The character of the Buddha in these traditional biographies is often that of a fully transcendent (Skt. lokottara) and perfected being who is unencumbered by the mundane world. In the Mahāvastu, over the course of many lives, Gautama is said to have developed supramundane abilities including: a painless birth conceived without intercourse; no need for sleep, food, medicine, or bathing, although engaging in such “in conformity with the world”; omniscience, and the ability to “suppress karma.”[9] Nevertheless, some of the more ordinary details of his life have been gathered from these traditional sources. In modern times there has been an attempt to form a secular understanding of Siddhārtha Gautama’s life by omitting the traditional supernatural elements of his early biographies.

The ancient Indians were generally unconcerned with chronologies, being more focused on philosophy. Buddhist texts reflect this tendency, providing a clearer picture of what Gautama may have taught than of the dates of the events in his life. These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha’s time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.[10][Full citation needed] Karen Armstrong writes that although there is very little information that can be considered historically sound, we can be reasonably confident that Siddhārtha Gautama did exist as a historical figure.[11] Michael Carrithers goes a bit further by stating that the most general outline of “birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death” must be true.[12][Full citation needed]

Conception and birth

Gautama is thought to have been born in Lumbini, in modern day Nepal[13] and raised in the small kingdom or principality of Kapilvastu.[14] At the time of his birth, the area was at, or beyond, the boundary of Vedic civilization, the dominant culture of northern India at the time. It is possible that his mother tongue was not an Indo-Aryan language.[15]

Early texts suggest that Gautama was not familiar with the dominant religious teachings of his time until he left on his religious quest, which is said to have been motivated by existential concern for the human condition.[16] At the time, many small city-states existed in Ancient India, called Janapadas. Republics and chiefdoms with diffused political power and limited social stratification, were not uncommon amongst them, and were referred to as gana-sanghas.[17] The Buddha’s community does not seem to have had a caste system. It was not a monarchy, and seems to have been structured either as an oligarchy, or as a form of republic.[18] The more egalitarian gana-sangha form of government, as a political alternative to the strongly hierarchical kingdoms, may have influenced the development of the Shramana type Jain and Buddhist sanghas, where monarchies tended toward Vedic Brahmanism.[19]

According to the most traditional biography,[which?] the Buddha’s father was King Suddhodana, the leader of Shakya clan, whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha’s lifetime; Gautama was the family name. His mother, Queen Maha Maya (Māyādevī) and Suddhodana’s wife, was a Koliyan princess. Legend has it that, on the night Siddhartha was conceived, Queen Maya dreamt that a white elephant with six white tusks entered her right side,[20] and ten months later Siddhartha was born. As was the Shakya tradition, when his mother Queen Maya became pregnant, she left Kapilvastu for her father’s kingdom to give birth. However, her son is said to have been born on the way, at Lumbini, in a garden beneath a sal tree.

The day of the Buddha’s birth is widely celebrated in Theravada countries as Vesak.[21] Various sources hold that the Buddha’s mother died at his birth, a few days or seven days later. The infant was given the name Siddhartha (Pāli: Siddhattha), meaning “he who achieves his aim”. During the birth celebrations, the hermit seer Asita journeyed from his mountain abode and announced that the child would either become a great king (chakravartin) or a great holy man.[22] By traditional account,[which?] this occurred after Siddhartha placed his feet in Asita’s hair and Asita examined the birthmarks. Suddhodana held a naming ceremony on the fifth day, and invited eight brahmin scholars to read the future. All gave a dual prediction that the baby would either become a great king or a great holy man.[22] Kaundinya (Pali: Kondanna), the youngest, and later to be the first arahant other than the Buddha, was reputed to be the only one who unequivocally predicted that Siddhartha would become a Buddha.[23]

While later tradition and legend characterized Śuddhodana as a hereditary monarch, the descendant of the Solar Dynasty of Ikṣvāku (Pāli: Okkāka), many scholars think that Śuddhodana was the elected chief of a tribal confederacy.

Early life and marriage

Siddhartha was brought up by his mother’s younger sister, Maha Pajapati.[24] By tradition, he is said to have been destined by birth to the life of a prince, and had three palaces (for seasonal occupation) built for him. Although more recent scholarship doubts this status, his father, said to be King Śuddhodana, wishing for his son to be a great king, is said to have shielded him from religious teachings and from knowledge of human suffering.

When he reached the age of 16, his father reputedly arranged his marriage to a cousin of the same age named Yaśodharā (Pāli: Yasodharā). According to the traditional account,[which?] she gave birth to a son, named Rahula. Siddhartha is then said to have spent 29 years as a prince in Kapilavastu. Although his father ensured that Siddhartha was provided with everything he could want or need, Buddhist scriptures say that the future Buddha felt that material wealth was not life’s ultimate goal.[24]

Departure and ascetic life

This scene depicts the “Great Departure” of Sidhartha Gautama, a predestined being. He appears here surrounded by a halo, and accompanied by numerous guards, mithuna loving couples, and devata, come to pay homage.[25] Gandhara art, Kushan period(1st-3rd century CE)

Prince Siddharta shaves his hair and become an ascetic. Borobudur, 8th century.

At the age of 29, the popular biography continues, Siddhartha left his palace to meet his subjects. Despite his father’s efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and suffering, Siddhartha was said to have seen an old man. When his charioteer Channa explained to him that all people grew old, the prince went on further trips beyond the palace. On these he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome ageing, sickness, and death by living the life of an ascetic.[26]

Accompanied by Channa and aboard his horse Kanthaka, Guatama quit his palace for the life of a mendicant. It’s said that, “the horse’s hooves were muffled by the gods”[27] to prevent guards from knowing of the new bodhisattva’s departure. This event is traditionally known as “the great departure”.

Guatama initially went to Rajagaha and began his ascetic life by begging for alms in the street. Having been recognised by the men of King Bimbisara, Bimbisara offered him the throne after hearing of Siddhartha’s quest. Siddhartha rejected the offer, but promised to visit his kingdom of Magadha first, upon attaining enlightenment.

He left Rajagaha and practised under two hermit teachers. After mastering the teachings of Alara Kalama (Skr. Ārāḍa Kālāma), he was asked by Kalama to succeed him. However, Guatama felt unsatisfied by the practise, and moved on to become a student of Udaka Ramaputta (Skr. Udraka Rāmaputra). With him he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness, and was again asked to succeed his teacher. But, once more, he was not satisfied, and again moved on.[28]

Siddhartha and a group of five companions led by Kaundinya are then said to have set out to take their austerities even further. They tried to find enlightenment through deprivation of worldly goods, including food, practising self-mortification. After nearly starving himself to death by restricting his food intake to around a leaf or nut per day, he collapsed in a river while bathing and almost drowned. Siddhartha began to reconsider his path. Then, he remembered a moment in childhood in which he had been watching his father start the season’s plowing. He attained a concentrated and focused state that was blissful and refreshing, the jhāna.

Enlightenment

The Buddha sitting in meditation, surrounded by demons of Māra. Sanskrit manuscript. Nālandā, Bihar, India. Pāla period.

According to the early Buddhist texts,[29] after realizing that meditative jhana was the right path to awakening, but that extreme asceticism didn’t work, Gautama discovered what Buddhists call the Middle Way[29]—a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.[29] In a famous incident, after becoming starved and weakened, he is said to have accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata.[30] Such was his emaciated appearance that she wrongly believed him to be a spirit that had granted her a wish.[30]

Following this incident, Gautama was famously seated under a pipal tree – now known as the Bodhi tree – in Bodh Gaya, India, when he vowed never to arise until he had found the truth.[31] Kaundinya and four other companions, believing that he had abandoned his search and become undisciplined, left. After a reputed 49 days of meditation, at the age of 35, he is said to have attained Enlightenment.[31][32] According to some traditions, this occurred in approximately the fifth lunar month, while, according to others, it was in the twelfth month. From that time, Gautama was known to his followers as the Buddha or “Awakened One.” (“Buddha” is also sometimes translated as “The Enlightened One.”) He is often referred to in Buddhism as Shakyamuni Buddha, or “The Awakened One of the Shakya Clan.”

According to Buddhism, at the time of his awakening he realized complete insight into the cause of suffering, and the steps necessary to eliminate it. These discoveries became known as the “Four Noble Truths“,[32] which are at the heart of Buddhist teaching. Through mastery of these truths, a state of supreme liberation, or Nirvana, is believed to be possible for any being. The Buddha described Nirvāna as the perfect peace of a mind that’s free from ignorance, greed, hatred and other afflictive states,[32] or “defilements” (kilesas). Nirvana is also regarded as the “end of the world”, in that no personal identity or boundaries of the mind remain. In such a state, a being is said to possess the Ten Characteristics, belonging to every Buddha.

According to a story in the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1) – a scripture found in the Pāli and other canons – immediately after his awakening, the Buddha debated whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance, greed and hatred that they could never recognise the path, which is subtle, deep and hard to grasp. However, in the story, Brahmā Sahampati convinced him, arguing that at least some will understand it. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

Formation of the sangha

Painting of the first sermon depicted at Wat Chedi Liem in Thailand.

After his awakening, the Buddha met two merchants, named Tapussa and Bhallika, who became his first lay disciples. They were apparently each given hairs from his head, which are now claimed to be enshrined as relics in the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma. The Buddha intended to visit Asita, and his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta, to explain his findings, but they had already died.

He then travelled to the Deer Park near Vārāṇasī (Benares) in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the five companions with whom he had sought enlightenment. Together with him, they formed the first saṅgha: the company of Buddhist monks.

All five become arahants, and within the first two months, with the conversion of Yasa and fifty four of his friends, the number of such arahants is said to have grown to 60. The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, with their reputed 200, 300 and 500 disciples, respectively. This swelled the sangha to more than 1000.

Travels and teaching

For the remaining 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to outcaste street sweepers, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka. From the outset, Buddhism was equally open to all races and classes, and had no caste structure, as was the rule in Hinduism. Although the Buddha’s language remains unknown, it’s likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The sangha traveled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the vassana rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely traveled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Mahamoggallana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the Buddha’s two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, capital of Magadha.

Upon hearing of his son’s awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message, and instead joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama’s (who also became an arahant), however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the Buddha, saying:

“Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms”

The Buddha is said to have replied:

“That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms”

Buddhist texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha’s cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant.

Of the Buddha’s disciples, Sariputta, Mahamoggallana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him. His ten foremost disciples were reputedly completed by the quintet of Upali, Subhoti, Rahula, Mahakaccana and Punna.

In the fifth vassana, the Buddha was staying at Mahavana near Vesali when he heard news of the impending death of his father. He is said to have gone to Suddhodana and taught the dharma, after which his father became an arahant.

The king’s death and cremation was to inspire the creation of an order of nuns. Buddhist texts record that the Buddha was reluctant to ordain women. His foster mother Maha Pajapati, for example, approached him, asking to join the sangha, but he refused. Maha Pajapati, however, was so intent on the path of awakening that she led a group of royal Sakyan and Koliyan ladies, which followed the sangha on a long journey to Rajagaha. In time, after Ananda championed their cause, the Buddha is said to have reconsidered and, five years after the formation of the sangha, agreed to the ordination of women as nuns. He reasoned that males and females had an equal capacity for awakening. But he gave women additional rules (Vinaya) to follow.

Assassination attempts

According to colorful legends, even during the Buddha’s life the sangha was not free of dissent and discord. For example, Devadatta, a cousin of Gautama who became a monk but not an arahant, more than once tried to kill him.

Initially, Devadatta is alleged to have often tried to undermine the Buddha. In one instance, according to stories, Devadatta even asked the Buddha to stand aside and let him lead the sangha. When this failed, he is accused of having three times tried to kill his teacher. The first attempt is said to have involved him hiring a group of archers to shoot the awakened one. But, upon meeting the Buddha, they laid down their bows and instead became followers. A second attempt is said to have involved Devadatta rolling a boulder down a hill. But this hit another rock and splintered, only grazing the Buddha’s foot. In the third attempt, Devadatta is said to have got an elephant drunk and set it loose. This ruse also failed.

After his lack of success at homicide, Devadatta is said to have tried to create a schism in the sangha, by proposing extra restrictions on the vinaya. When the Buddha again prevailed, Devadatta started a breakaway order. At first, he managed to convert some of the bhikkhus, but Sariputta and Mahamoggallana are said to have expounded the dharma so effectively that they were won back.

Mahaparinirvana

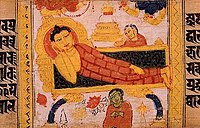

The Buddha’s entry into Parinirvana. Sanskrit manuscript. Nālandā, Bihar, India. Pāla period.

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body. After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha.[33] Mettanando and von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of mesenteric infarction, a symptom of old age, rather than food poisoning.[34] The precise contents of the Buddha’s final meal are not clear, due to variant scriptural traditions and ambiguity over the translation of certain significant terms; the Theravada tradition generally believes that the Buddha was offered some kind of pork, while the Mahayana tradition believes that the Buddha consumed some sort of truffle or other mushroom. These may reflect the different traditional views on Buddhist vegetarianism and the precepts for monks and nuns.

Ananda protested the Buddha’s decision to enter Parinirvana in the abandoned jungles of Kuśināra (present-day Kushinagar, India) of the Malla kingdom. Buddha, however, is said to have reminded Ananda how Kushinara was a land once ruled by a righteous wheel-turning king that resounded with joy:

44. Kusavati, Ananda, resounded unceasingly day and night with ten sounds—the trumpeting of elephants, the neighing of horses, the rattling of chariots, the beating of drums and tabours, music and song, cheers, the clapping of hands, and cries of “Eat, drink, and be merry!”

The Buddha then asked all the attendant Bhikshus to clarify any doubts or questions they had. They had none. According to Buddhist scrptures, he then finally entered Parinirvana. The Buddha’s final words are reported to have been: “All composite things pass away. Strive for your own liberation with diligence.” His body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present. For example, The Temple of the Tooth or “Dalada Maligawa” in Sri Lanka is the place where what some believe to be the relic of the right tooth of Buddha is kept at present.

According to the Pāli historical chronicles of Sri Lanka, the Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa, the coronation of Aśoka (Pāli: Asoka) is 218 years after the death of Buddha. According to two textual records in Chinese (十八部論 and 部執異論), the coronation of Aśoka is 116 years after the death of Buddha. Therefore, the time of Buddha’s passing is either 486 BCE according to Theravāda record or 383 BCE according to Mahayana record. However, the actual date traditionally accepted as the date of the Buddha’s death in Theravāda countries is 544 or 543 BCE, because the reign of Aśoka was traditionally reckoned to be about 60 years earlier than current estimates.

At his death, the Buddha is famously believed to have told his disciples to follow no leader. Mahakasyapa was chosen by the sangha to be the chairman of the First Buddhist Council, with the two chief disciples Mahamoggallana and Sariputta having died before the Buddha.

Physical characteristics

Gandhāran depiction of the Buddha from Hadda, Central Asia. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

An extensive and colorful physical description of the Buddha has been laid down in scriptures. A kshatriya by birth, he had military training in his upbringing, and by Shakyan tradition was required to pass tests to demonstrate his worthiness as a warrior in order to marry. He had a strong enough body to be noticed by one of the kings and was asked to join his army as a general. He is also believed by Buddhists to have “the 32 Signs of the Great Man”.

The Brahmin Sonadanda described him as “handsome, good-looking, and pleasing to the eye, with a most beautiful complexion. He has a godlike form and countenance, he is by no means unattractive.”(D,I:115).

“It is wonderful, truly marvellous, how serene is the good Gotama’s appearance, how clear and radiant his complexion, just as the golden jujube in autumn is clear and radiant, just as a palm-tree fruit just loosened from the stalk is clear and radiant, just as an adornment of red gold wrought in a crucible by a skilled goldsmith, deftly beaten and laid on a yellow-cloth shines, blazes and glitters, even so, the good Gotama’s senses are calmed, his complexion is clear and radiant.” (A,I:181)

A disciple named Vakkali, who later became an Arahant, was so obsessed by Buddha’s physical presence that the Buddha is said to have felt impelled tell him to desist, and to have reminded him that he should know the Buddha through the Dhamma and not through physical appearances.

Although there are no extant representations of the Buddha in human form until around the 1st century CE (see Buddhist art), descriptions of the physical characteristics of fully enlightened buddhas are attributed to the Buddha in the Digha Nikaya‘s Lakkhaṇa Sutta (D,I:142).[35] In addition, the Buddha’s physical appearance is described by Yasodhara to their son Rahula upon the Buddha’s first post-Enlightenment return to his former princely palace in the non-canonical Pali devotional hymn, Narasīha Gāthā (“The Lion of Men”).[36]

Teachings

Some scholars believe that some portions of the Pali Canon and the Āgamas contain the actual substance of the historical teachings (and possibly even the words) of the Buddha.[37][38] This is not the case for the later Mahāyāna sūtras.[39] The scriptural works of Early Buddhism precede the Mahayana works chronologically, and are treated by many Western scholars as the main credible source for information regarding the actual historical teachings of Gautama Buddha. However, some scholars do not think that the texts report on historical events.[40][41][42]

Some of the fundamentals of the teachings attributed to Gautama Buddha are:

- The Four Noble Truths: that suffering is an ingrained part of existence; that the origin of suffering is craving for sensuality, acquisition of identity, and annihilation; that suffering can be ended; and that following the Noble Eightfold Path is the means to accomplish this.

- The Noble Eightfold Path: right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

- Dependent origination: the mind creates suffering as a natural product of a complex process.

- Rejection of the infallibility of accepted scripture: Teachings should not be accepted unless they are borne out by our experience and are praised by the wise. See the Kalama Sutta for details.

- Anicca (Sanskrit: anitya): That all things that come to be have an end.

- Dukkha (Sanskrit: duḥkha): That nothing which comes to be is ultimately satisfying.

- Anattā (Sanskrit: anātman): That nothing in the realm of experience can really be said to be “I” or “mine”.

- Nibbāna (Sanskrit: Nirvāna): It is possible for sentient beings to realize a dimension of awareness which is totally unconstructed and peaceful, and end all suffering due to the mind’s interaction with the conditioned world.

However, in some Mahayana schools, these points have come to be regarded as more or less subsidiary. There is disagreement amongst various schools of Buddhism over more complex aspects of what the Buddha is believed to have taught, and also over some of the disciplinary rules for monks.

According to tradition, the Buddha emphasized ethics and correct understanding. He questioned everyday notions of divinity and salvation. He stated that there is no intermediary between mankind and the divine; distant gods are subjected to karma themselves in decaying heavens; and the Buddha is only a guide and teacher for beings who must tread the path of Nirvāṇa (Pāli: Nibbāna) themselves to attain the spiritual awakening called bodhi and understand reality. The Buddhist system of insight and meditation practice is not claimed to have been divinely revealed, but to spring from an understanding of the true nature of the mind, which must be discovered by treading the path guided by the Buddha’s teachings.

Other religions

Gautama Buddha is also described as a god or prophet in other religions. Some Hindu texts say that the Buddha was an avatar of the god Vishnu, who came to Earth to delude beings away from the Vedic religion.[43]

The Buddha is also regarded as a prophet by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community[44][45] and a Manifestation of God in the Bahá’í faith.[46] Some early Chinese Taoist-Buddhists thought the Buddha to be a reincarnation of Lao Tzu.[47]

See also

|

References

- Notes

- ^ Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley (1962–1985). “buddha 9276”. A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages. London: Oxford University Press. Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago. p. 525. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/contextualize.pl?p.2.soas.1976481. Retrieved 22 February 2010. “Hypothetical root budh ‘ perceive ’ 1. Pali buddha – ‘ understood, enlightened ’, masculine ‘ the Buddha ’; Aśokan, that is, the language of the Inscriptions of Aśoka Budhe nominative singular; Prakrit buddha – ‘ known, awakened ’; Waigalī būdāī ‘ truth ’; Bashkarīk budh ‘ he heard ’; Tōrwālī būdo preterite of bū – ‘ to see, know ’ from bṓdhati; Phalūṛa búddo preterite of buǰǰ – ‘ to understand ’ from búdhyatē; Shina Gilgitī dialect budo ‘ awake ’, Gurēsī dialect budyōnṷ intransitive ‘ to wake ’; Kashmiri bọ̆du ‘ quick of understanding (especially of a child ’); Sindhī ḇudho past participle (passive) of ḇujhaṇu ‘ to understand ’ from búdhyatē, West Pahāṛī buddhā preterite of bujṇā ‘ to know ’; Sinhalese buj (j written for d), budu, bud – , but – ‘ the Buddha ’.”

- References

- ^ “The Buddha, His Life and Teachings”. Buddhanet.net. http://www.buddhanet.net/buddha.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ^ L. S. Cousins (1996), “The dating of the historical Buddha: a review article”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (3)6(1): 57–63.

- ^ See the consensus in the essays by leading scholars in The Date of the Historical Śākyamuni Buddha (2003) Edited by A. K. Narain. B. R. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7646-353-1.

- ^ “If, as is now almost universally accepted by informed Indological scholarship, a re-examination of early Buddhist historical material, …, necessitates a redating of the Buddha’s death to between 411 and 400 BCE….: Paul Dundas, The Jains, 2nd edition, (Routledge, 2001), p. 24.

- ^ a b Fowler, Mark. Zen Buddhism: beliefs and practices. Sussex Academic Press. 2005. p. 32

- ^ a b Karetzky, Patricia. Early Buddhist Narrative Art. 2000. p. xxi

- ^ Swearer, Donald. Becoming the Buddha. 2004. p. 177

- ^ Schober, Juliane. Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. 2002. p. 20

- ^ Jones, J.J. The Mahāvastu (3 vols.) in Sacred Books of the Buddhists. London: Luzac & Co. 1949–56.

- ^ Carrithers, page 15.

- ^ Armstrong, Karen (2000). Buddha. Orion. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-7538-1340-9.

- ^ Carrithers, page 10.

- ^ “Buddhanet.net”. Buddhanet.net. http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/lumbini.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ^ “UNESCO.org”. Whc.unesco.org. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/666. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ^ Richard Gombrich, Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988, page 49.

- ^ Sue Hamilton, Early Buddhism: A New Approach: The I of the Beholder. Routledge 2000, page 47.

- ^ Romila Thapar, The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books, 2002, page 137.

- ^ Richard Gombrich, Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988, pages 49-50.

- ^ Romila Thapar, The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books, 2002, page 146.

- ^ “Sacred-texts.com”. Sacred-texts.com. http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/lob/lob04.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ^ Turpie, D. 2001. Wesak And The Re-Creation of Buddhist Tradition. Master’s Thesis. Montreal, Quebec: McGill University. (p. 3). Available from: Mcgill.ca. Retrieved 17 November 2006.

- ^ a b Narada (1992). A Manual of Buddhism. Buddha Educational Foundation. p. 9–12. ISBN 967-9920-58-5.

- ^ Narada (1992), p11-12

- ^ a b Narada (1992), p14

- ^ Guimet.fr

- ^ Conze (1959), pp39-40

- ^ Narada (1992), pp15-16

- ^ Narada (1992), pp19-20

- ^ a b c Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion

- ^ a b The Golden Bowl

- ^ a b Gyatso, Geshe Kelsang (2007). Introduction to Buddhism An Explanation of the Buddhist Way of Life. Tharpa. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-9789067-7-1.

- ^ a b c The Basic Teaching of Buddha

- ^ Maha-parinibbana Sutta (DN 16), verse 56

- ^ Mettanando Bhikkhu and Oskar von Hinueber, “The Cause of the Buddha’s Death”; Vol. XXVI of the Journal of the Pali Text Society, 2000. See also this article by Mettanando saying the same thing: Buddhanet.net.

- ^ Maurice Walshe, The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya, 1995, Boston: Wisdom Publications, “[DN] 30: Lakkhaṇa Sutta: The Marks of a Great Man,” pp. 441-60.

- ^ Ven. Elgiriye Indaratana Maha Thera, Vandana: The Album of Pali Devotional Chanting and Hymns, 2002, pp. 49-52, retrieved 2007-11-08 from Buddhanet.net

- ^ It is therefore possible that much of what is found in the Suttapitaka is earlier than c.250 B.C., perhaps even more than 100 years older than this. If some of the material is so old, it might be possible to establish what texts go back to the very beginning of Buddhism, texts which perhaps include the substance of the Buddha’s teaching, and in some cases, maybe even his words. How old is the Suttapitaka? Alexander Wynne, St John’s College, 2003, p.22 (this article is available on the website of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies: [www.ocbs.org/research/Wynne.pdf]

- ^ It would be hypocritical to assert that nothing can be said about the doctrine of earliest Buddhism … the basic ideas of Buddhism found in the canonical writings could very well have been proclaimed by him [the Buddha], transmitted and developed by his disciples and, finally, codified in fixed formulas. J.W. De Jong, 1993: The Beginnings of Buddhism, in The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 26, no. 2, p. 25

- ^ The Mahayana movement claims to have been founded by the Buddha himself. The consensus of the evidence, however, is that it originated in South India in the 1st century CE–Indian Buddhism, AK Warder, 3rd edition, 1999, p. 335.

- ^ Bareau, André, Les récits canoniques des funérailles du Buddha et leurs anomalies : nouvel essai d’interprétation, BEFEO, t. LXII, Paris, 1975, pp.151-189.

- ^ Bareau, André, La composition et les étapes de la formation progressive du Mahaparinirvanasutra ancien, BEFEO, t. LXVI, Paris, 1979, pp. 45-103.

- ^ Shimoda, Masahiro, How has the Lotus Sutra Created Social Movements: The Relationship of the Lotus Sutra to the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra, in A Buddhist Kaleidoscope, (pp320-22) Ed Gene Reves, Kosei 2002

- ^ Nagendra Kumar Singh (1997). “Buddha as depicted in the Purāṇas”. Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Volume 7. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD.. pp. 260–275. ISBN 9788174881687. http://books.google.com/?id=UG9-HZ5icQ4C&pg=PA260 . List of Hindu scripture that declares Gautama Buddha as 9th Avatar of Vishnu as as follows [Harivamsha (1.41) Vishnu Purana (3.18) Bhagavata Purana (1.3.24, 2.7.37, 11.4.23 Bhagavata Purana 1.3.24 Bhagavata Purana 1.3.24, Garuda Purana (1.1, 2.30.37, 3.15.26) Agni Purana (160.Narada Purana (2.72)Linga Purana (2.71) Padma Purana (3.252) etc. Bhagavata Purana, Canto 1, Chapter 3 – SB 1.3.24: “Then, in the beginning of Kali-yuga, the Lord will appear as Lord Buddha, the son of Anjana, in the province of Gaya, just for the purpose of deluding those who are envious of the faithful theist.” … The Bhavishya Purana contains the following: “At this time, reminded of the Kali Age, the god Vishnu became born as Gautama, the Shakyamuni, and taught the Buddhist dharma for ten years. Then Shuddodana ruled for twenty years, and Shakyasimha for twenty. At the first stage of the Kali Age, the path of the Vedas was destroyed and all men became Buddhists. Those who sought refuge with Vishnu were deluded.” Found in Wendy O’Flaherty, Origins of Evil in Hindu Mythology. University of California Press, 1976, page 203. Note also SB 1.3.28: “All of the above-mentioned incarnations [avatars] are either plenary portions or portions of the plenary portions of the Lord [Krishna or Vishnu]”

- ^ “Buddhism”. http://www.alislam.org/library/books/revelation/part_2_section_2.html. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ “An Overview”. Alislam. http://www.alislam.org/introduction/index.html. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). “Manifestations of God”. A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá’í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 231. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ The Cambridge History of China, Vol.1, (The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 BC—220 BC) ISBN 0-521-24327-0 hardback

Further reading

- Ambedkar, B.R. The Buddha and His Dhamma, 1957.

- Armstrong, Karen. Buddha. (New York: Penguin Books, 2001).

- Bechert, Heinz (ed.) (1996) When Did the Buddha Live? The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Delhi: Sri Satguru.

- Conze, Edward (translator). Buddhist Scriptures. (London: Penguin Books, 1959).

- Sathe, Shriram: Dates of the Buddha. Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, Hyderabad 1987.

- Susan Roth: Buddha. (New York: Delacorte Press, 1994).

- Deepak Chopra: Buddha. (Newsarama, 2008).

- Jon Ortner: Buddha. (New York: Welcome Books, 2003).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Gautama Buddha |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Gautama Buddha |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Gautama Buddha |

References

- “Buddha.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 07 Jan. 2011. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/83105/Buddha>.

Categories: Buddhism, CHRISTIANITY, Islam, Religion

Hinduism, Buddhism and Jesus

This is a comment by Mohammad Durgauhee from Google knol

Through a dialogue with a Hindu friend of mine recently, this question arose:

A concept of ten avtars exists amongst Hindus, whereby the 7th avtar is classified as Ram (a.s), the 8th as Krishna (a.s), the 9th as Buddha (a.s) and the 10th, who is yet to come according to Hindus, as the Kalki avtar.

Question: If Hindus recognize Buddha (a.s) as an avtar, why do Buddhism and Hinduism seem to be separate religions?

Secondly, Buddha (a.s) seems to have predicted the advent of Metteya Buddha (as we read from Hadhrat Massih Mawood (a.s)’s book ‘Jesus in India), which we in Islam-Ahmadiyyat, believe to be Jesus (a.s). This seems to imply that Jesus (a.s) seems to be a link between Buddhists (and hence Hindus) and Israelites. Am I right in this conclusion?

Jazakumullah for any further help around this subject.

Bait and switch a common Christian strategy

Bait and switch is commonly employed consciously or unconsciously by the Christian apologists to defend all their dogma, they present the proofs and need of One God and then sell to the naive three persons in one being of Trinity, without offering any proof for the Triune God. For example recently the Pope Benedict XVI made some news, about the need of a Creator and then implying a Triune God without any evidence for that. It was reported:

God’s mind was behind complex scientific theories such as the Big Bang, and Christians should reject the idea that the universe came into being by accident, Pope Benedict said.

“The universe is not the result of chance, as some would want to make us believe,” Benedict said on the day Christians mark the Epiphany, the day the Bible says the three kings reached the site where Jesus was born by following a star.

“Contemplating it (the universe) we are invited to read something profound into it: the wisdom of the creator, the inexhaustible creativity of God,” he said in a sermon to some 10,000 people in St Peter’s Basilica on the feast day.

While the pope has spoken before about evolution, he has rarely delved back in time to discuss specific concepts such as the Big Bang, which scientists believe led to the formation of the universe some 13.7 billion years ago.

http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20110106/lf_nm_life/us_pope_bigbang

This universe with its unifying principles speaks of one Creator and not three! This point has been argued in some detail in the following publication:

http://www.alislam.org/egazette/eGazette-Nov2008.pdf

Referring to the comment entitled ‘Hinduism, Buddhism and Jesus’ where we can read “Buddha (a.s) seems to have predicted the advent of Metteya Buddha (as we read from Hadhrat Massih Mawood (a.s)’s book ‘Jesus in India), which we in Islam-Ahmadiyyat, believe to be Jesus (a.s). This seems to imply that Jesus (a.s) seems to be a link between Buddhists (and hence Hindus) and Israelites.”, I further noted the following extract from the book ‘An Elementary Study of Islam’ by Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (r.h):

“Dhul-Kifl is one name in the list of prophets which is unheard of in the Arab or Semitic references. Some scholars seem to have traced this name to Buddha, who was of Kapeel, which was the capital of a small state situated on the border of India and Nepal. Buddha not only belonged to Kapeel, but was many a time referred to as being ‘Of Kapeel’. This is exactly what is meant by the word ‘Dhul-Kifl’. It should be remembered that the consonant ‘p’ is not present in Arabic, and the nearest one to it is ‘fa’. Hence, Kapeel transliterated into Arabic becomes Kifl.”

(http://www.alislam.org/books/study-of-islam/prophets.html)

Elsewhere, we find Dhul Kifl referred to as Ezekiel (a.s) who seems to be of israelite origin. Would that imply that Buddha (a.s) could be of israelite origin, which would resolve the puzzle about Jesus (a.s) being a prophet for the lost tribes of the house of israel and hence could preach to the followers of Buddha (a.s) and his advent could have been predicted by Buddha (a.s)?